It's a rarity to witness a fashion design graduate transition into the world of weaving, committing their life to the advancement of Indian textiles. Yet, Hemang Agrawal stands as a prime example of such a journey.

Hemang Agrawal completed his fashion design education in 2001 at the National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT) in Mumbai. Born into a Varanasi-based textile family, the essence of handloom silks was ingrained in his daily life. His father, Shyam Krishna Agrawal, a fine arts student well-versed in both art and business, established Surekha Arts in 1970—a firm under the Surekha Group banner—specializing in saris. Thus, textiles became an integral part of Hemang's consciousness, shaping his life from its inception.

His reasoning is rooted in the nature of textile crafts. Unlike fashion, the identity of a craft must surpass that of its practitioners. Agrawal illustrates this by comparing Indian miniature paintings, which are identified by their schools, to Western art movements that are often associated with individual painters.

Following his graduation, Agrawal spent 18 months as the head designer for Contemporary Clothing Company Mumbai, a garment export house, before freelancing as a designer to gain practical experience. In 2003, he returned to Varanasi and trained at the Indian Institute of Handloom Technology.

The subsequent year marked Agrawal's entry into the family business. His younger brother, Umang, an investment banker at S&P in the US, followed suit six years later.

Armed with a fashion design background, Agrawal possessed a unique perspective on textiles from a fashion standpoint, which significantly aided his development and design efforts. From the outset, he concentrated on crafting premium and super-fine hand-woven silk textiles for international markets, infusing tradition with contemporary flair. Agrawal spent the first two years of his tenure visiting weavers, dyers, naqshnbands, and card punchers—craftsmen his father collaborated with for the saree business. Simultaneously, he crossed paths with Rahul Jain, a prominent textile historian and revivalist, whose guidance and inspiration further propelled him into the realm of handloom textiles. This period marked Agrawal's immersion into the world of silk, and he proudly claims to be half a proficient weaver himself.

Explaining the weaving programme of the company, Agrawal says, "Benares is not a back-integrated industry. There are no factory set-ups where looms are erected and people come and work by man-hours. The weavers work mostly from their own homes. We have approximately 600 weaving households associated with us, some running just 1-2 looms and others running a lot more. We have a team of about 50 people supporting the design, quality and logistics."

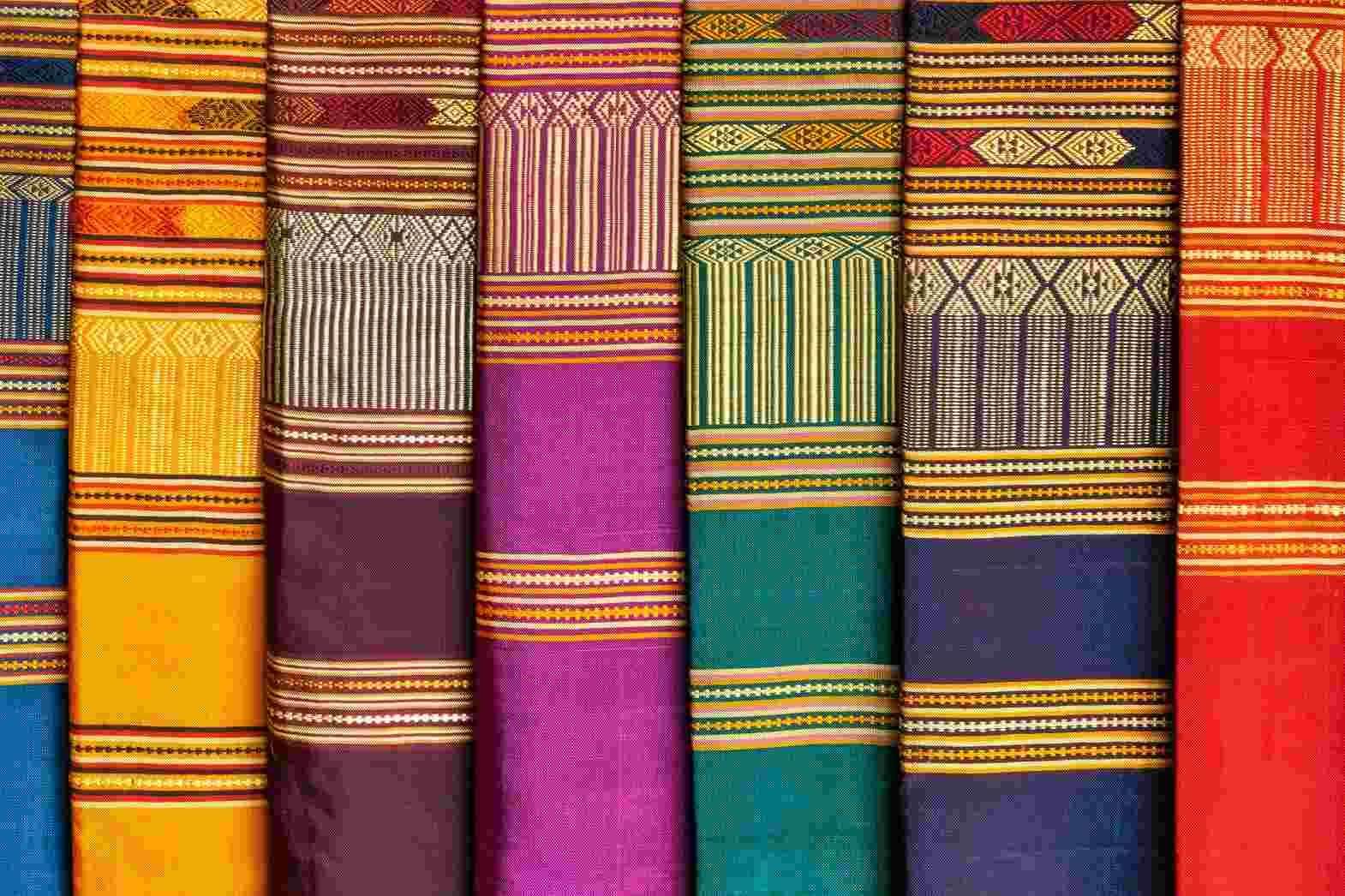

The range of fabrics that are woven is an amazing variety as Agrawal reveals, "You could identify them as brocades. But within that, we do an incredible range of textiles from tanchois to kimkhwaabs, from gethuas to jamavars, from cutworks to karhuans, and all of them using not only mulberry silk but wool, cotton, wild silks, linen, zari, stainless steel, modal, viscose, polyester and several types of yarns. In fact, some of the fabrics are so avant-garde and international that you will find it hard to believe that they were woven on simple pit looms in Benares. We have both handlooms and powerlooms. All our pure silk textiles are done on handlooms. Our powerlooms predominantly cater to the price-sensitive B2B segment, which is a significant market that one cannot ignore. Quantitatively, powerlooms would be about 70 per cent, but in value terms, it still remains 60 per cent handlooms and 40 per cent powerlooms."

With a current capacity of about 8,000 metres per day, the textiles division of the company has a turnover of $2 million while the overall group turnover is $10 million. "Of late, we have been collaborating with some international and Indian designers and brands. We have also ventured into retail with our store Seasons by Surekha Arts and our website www.holyweaves.com," says Agrawal, who now serves as the managing director of the company.

Going international

Agrawal used to travel a lot for trade shows and to meet buyers both within the country and abroad till about 2007. "The fact that we do premium textiles, which have a constraint both in terms of production and the number of people one can cater to, and also that we have been lucky in having more orders than our production capacities, has meant that travel in the last few years has been more for R&D than for marketing," he says.

When it comes to selling Indian textiles in the country and abroad, Agrawal observes, "India discovered itself as a big market only in the last two decades and we took ourselves seriously after the 2001 and 2008 global meltdowns. Earlier, every textile and garment company wanted to be a 100 per cent EOU. But today, for mass-produced textiles, India is obviously the biggest and easiest market. The only issue is, we are not as quality conscious as the West because of which, in the premium textiles segment, we still have to concentrate on Western countries for demand."

And what does he do towards this? Agrawal elaborates, "We do some very contemporary stoles and textiles using age-old weaving techniques of Benares in pure silver and gold yarns. They are quite successful in Japan and Europe. Also, we work closely with some very big names in international fashion for their textile development. These items don't form a very significant part of the turnover, may be 5 per cent or so, but the satisfaction one gets out of these is immense."

Much needs to be done, still. Agrawal admits, "Sustainability and eco-friendly textiles is one field where Benares as an industry has to still go a long distance. This stems from the fact that Benares textiles cater to the Indian market that is not as concerned with green practices as compared to say, Germany or other European countries. Since we have worked with European partners, we have tried to regulate several aspects including the dye-stuffs used, the chemicals used in finishing post-loom, disposal of waste. But I would be very far from the truth if I said that everything we do is green."

Then there are the human resources. "Weavers in Benares mostly work from their own homes. You could call them freelancers. So, they tend to work with many people at any given point in time. Now, because we are very design-centric, we have to have dedicated artisans who do not freelance. In a way it becomes my responsibility towards my weavers that they do not have to be freelancers to survive and be successful. We are lucky that a majority of our master-weavers have been with us for more than 15 years. Instead of terming what we do as extremely innovative, I would call it just doing small things right. We pay wages, which are way above industry standards and fair value for their products along with continuous work throughout the year.

"All we need from them is quality as per our specifications and maintaining sanctity of our design process. For everyone working in any craft or cottage industry sector, the best form of CSR is where exponents stay with you not out of compulsion but out of choice. We understand that it is their skill, which is bearing fruits for us; so it's very important to share the dividends with the craftsmen and we do that through various initiatives. While we are nowhere close to a structured HR or CSR policy, I can proudly say that people working with us are a happy, satisfied, and smiling lot."

The present and the future

For someone heavily into promoting Indian textiles, Agrawal has his reservations about the government's earlier plan of amending the Handloom Act, which lists goods and textiles reserved for production by traditional crafts and weavers. "The idea was floated by the powerloom lobby who wanted to remove saris from the list of items protected by the Handloom Protection Act. While I can live with powerlooms aping handloom textiles because of various dynamics involved, I can't accept it being legitimised by the government. I am happy that the proposal has been put aside."

Agrawal feels that for a well-designed and good quality handloom product, the demand is currently several times more than what can be produced. "But when I talk of the whole industry, the mass market is moving towards cheap powerloom imitations, which brings up the topic of fake weaves from China and the fight against them. I do not see the issue like that. China has its own strengths when it comes to silk yarn and degummed greige silk fabrics such as georgettes. Our strength is value addition on the loom and post-loom. The segment that I operate in, China is not a competition."

He, however, feels that immediate steps must be taken to arrest the decay of art and craft in India. "This is a subject close to my heart, but it's a really long discussion. In a nutshell, I can say it needs a four-pronged approach. The government has to focus on support in marketing and skill development; designers have to work towards contemporarisation of product and designs, while respecting sanctity of the crafts and processes; businesses working in the field have to focus on better monetary rewards for craftsmen; and end customers have to be educated about the premium associated with handlooms and handicrafts and why their patronage is so important. Currently, there is some support from all of these four quarters, but it's entirely incoherent."

When it comes to the future of traditional textiles in India, Agrawal confesses that India is far behind China and other Asian countries when it comes to mill-made textiles and Western garments. "Our traditional textiles are our strongest suit. Our weaves and colours are our identity globally. Even our powerlooms survive because most of them produce fabrics, which resemble our handloom fabrics. If India has to have any future as a textiles producing country, it has to be through the traditional textiles route. The good thing is that there is a huge demand for traditional textiles in India and the sub-continental diaspora. Even Western designers, who have always been more interested in textures than motifs are using traditional Indian textiles, albeit they are a small lot."

So will the great art and craft of weaving be able to get fresh blood? "This is a concern. A majority of my weavers are 35 years and above in age. The young ones are simply not taking up the craft. The fault is entirely ours because as a country, we have not patronised and incentivised them enough over the years. As a result, the younger lot is moving to whichever profession they think is better monetarily. I do not fault them. In terms of younger generation of artists and designers, things are comparatively much more encouraging and there are several young people working in this field."

What about rising stars? Agrawal, who is connected with several fashion institutes in the country, has observed and judged the work of graduating fashion and textiles students and is optimistic about the future of textiles in the country. "I like the fact that more students today are willing to work in the sphere of Indian textiles and crafts. The problem is that these square pegs have to pass through the round holes of our design education due to which I see a lot of homogenous design language among students. If they can maintain their individuality, I think we will have a fine crop."

When it comes to his home town Varanasi as a place for business and his dreams for the future and why he hasn't started a label like other fashion graduates, the bachelor Agrawal has no time to think of anything but work. "I love this city. Though it's not particularly attuned to doing business and getting good quality manpower is always a constraint, I just love the energies this place has - which push me into doing more. My dreams are small. I am very lucky that I get to do for a living something that I am very passionate about. Maybe if we as a group keep on doing the right things, the right way, new paths may emerge. Though I was reasonably good at pattern making, draping and garment construction, my calling was always textiles. Most of the time, textiles tend to be ancillary to the product. So till now, I have been rather happy being the faceless craftsman. Also, it's only been ten years since I got into it. The day I think I'm ready I'll think about a label."

Comments