Theblock-printing style called 'ajrakh' is a legacy of the Indus ValleyCivilisation. Renu Gupta

Ajrakh is an ancientblock-printing method on textiles that originated in the presentday provincesof Sindh in Pakistan and the neighbouring Indian districts of Kutch in Gujaratand Barmer in Rajasthan. The word 'ajrakh' itself connotes a number ofdifferent concepts.

According to some, it comes fromthe Arabic word ajrakh, which means blue, one of the chief colours in ajrakhprinting. Other historians say the word has been coined from the two Hindiwords- aaj rakh, meaning, keep it today.

According to others, it meansmaking beautiful. Although ajrakh printing is a part of the culture of Sindh,its roots extended to the states of Rajasthan and Gujarat in India during thetimes of the Indus Valley Civilisation, around 3000 BC. The Indus river was animportant resource for washing fabric and sustenance of raw materials likeindigo dye and cotton, which were copious along the river.

Ajrakh printing thrived in Indiain the 16th century with the migration of Khatris from the Sindh province toKutch district. The king of Kutch acknowledged and recognized the textile art,and indirectly encouraged the migration of Khatris to uninhabited lands inKutch. Ultimately, some Khatri printer families migrated to Rajasthan andsettled in and around Barmer province of British India, including present-dayGujarat, and excelled at the art of ajrakh printing. At present, the Khatricommunity is engrossed in consistently producing jrakh printed fabric ofsupreme quality in Ajrakhpur village in Kutch and also Barmer.

Celebrationof nature

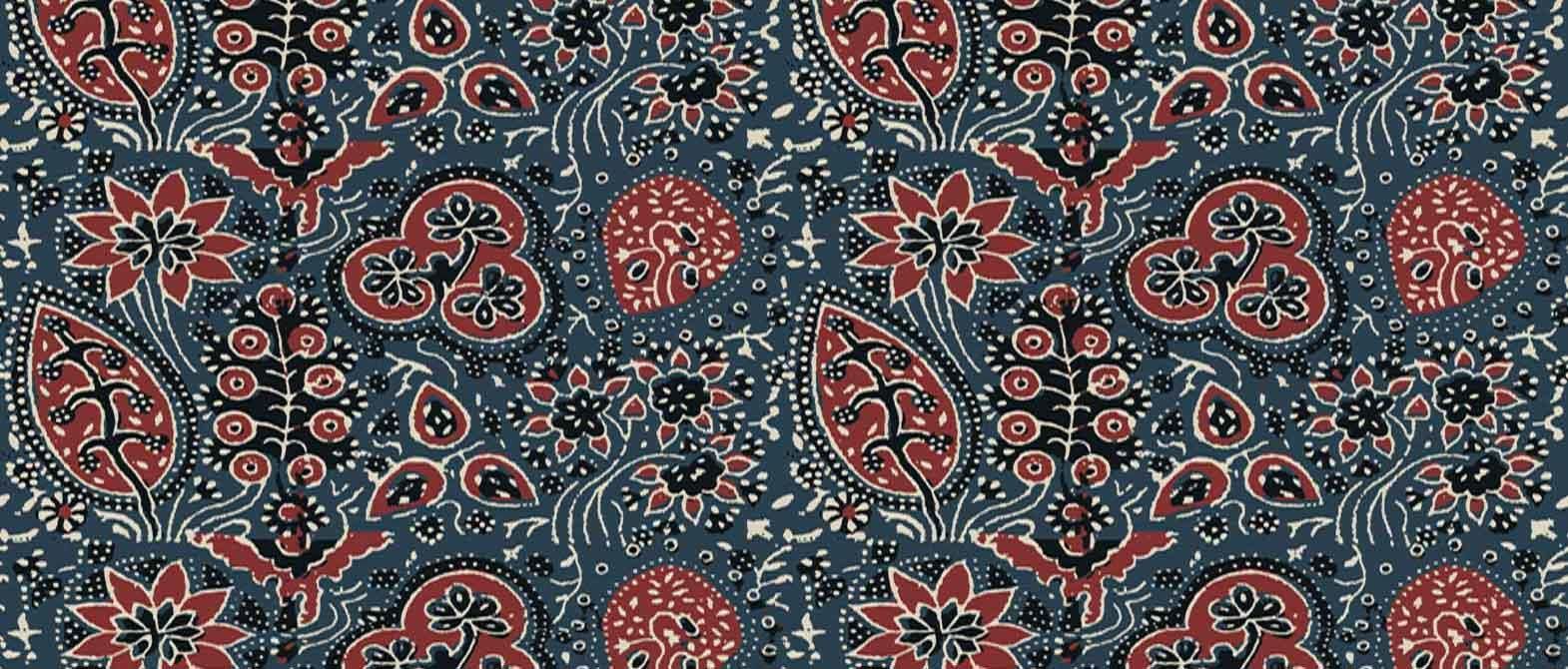

Ajrakh printing celebrates natureamazingly. This is evident in the aesthetics of the unification of its coloursas well as motifs.

The traditional colours found inajrakh printing are deep, which symbolise nature. Crimson red symbolizes theearth, and indigo blue symbolises twilight. Black and white are used with aview to outline motifs and define symmetrical designs. Although the use ofeco-friendly synthetic dyes is prevalent, the use of traditional natural dyesis being resumed gradually. Indigo is obtained from the indigo plant. Craftsmenused indigo plants growing profusely along the Indus river. Red is acquiredfrom alizarin found in the roots of madder plants. Black is obtained from ironshavings, millet flour and molasses with the addition of ground tamarind seedsto thicken the dye. The contemporary ajrakh prints have intensely vibrantcontrasting colours like rust, yellow and orange.

The use of traditional elaborate

motifs is still prevalent in ajrakh printing, which is the legacy of earlier

generations. These are symmetrically-geometric jewellike shapes symbolising

natural elements like flowers, leaves and stars. The most common motif found in

ajrakh printing is the trefoil which is thought to be made of three sundiscs

joined together to represent the cohesive unity of the gods of earth, water and

sun. All motifs are stamped around a central point and are repeated across the

fabric in a grid forming something akin to web-like design, or the central

jaal. This jaal is made of vertical, diagonal and horizontal lines. Besides

this web, border designs are also printed. The borders are aligned both

horizontally as well as vertically and frame the central portion,

distinguishing one ajrakh from another. A wider double margin is used to print

the lateral ends with a view to differentiate the layouts of borders.

Ajrakh is worn by males of the gypsy,

Jat and Meghwal communities. The men wear safa, a shoulder cloth and lungi.

People with lower incomes sport the ekpuri ajrakh, printed on one side. People

from higher income groups wear bipuri ajrakh, printed on both sides. This is

costlier, and is a status symbol. It is worn during ceremonies like weddings.

Men carry new ajrakh lungis at weddings as shoulder-wear. On Eid and other

special occasions, it is presented to bridegrooms. This craft is prevalent in

everyday usage, like bed spreads, hammocks, dupattas, scarves and even gifts

given as a token of honour.

Processing

ajrakh

Ajrakh printing is a long and

arduous process that requires a number of stages of printing and washing the

fabric repeatedly with different natural dyes and mordants. The technique of

resist printing is employed. This permits absorption of a dye in the required

areas and prohibits absorption on the areas meant not to be coloured. The

stages are elaborated below:

Saaj: The fabric is washed to

remove starch and then dipped in a solution of camel dung, soda ash and castor

oil. Next, it is wrung out and kept overnight. The next day, the fabric is

partially dried under the sun and then dipped in the solution again. This

process of saaj and drying is repeated about eight times until the fabric

produces foam when rubbed. Finally, it is washed in plain water.

Kasano: The fabric is washed in a

solution of myrobalan which is the nut from the harde tree. Myrobalan is used

as the first mordant in the dyeing process. Next, the fabric is dried under the

sun on both sides. The extra myrobalan on the fabric after drying is brushed

off.

Khariyanu: A resist of lime and

gum Arabic (babool tree resin) is printed on to the fabric to outline the

motifs that are required to be white. This outline printing is called rekh. The

resist is printed on both sides of fabric using carved wooden blocks.

Kat: Scrap iron and jaggery are mixed with water and left for about 20 days. The water becomes ferrous. Next, tamarind seed powder is added and the ferrous water is boiled to a paste known as kat and is printed on to both sides of the fabric.

Gach: Clay, alum and gum Arabic

are mixed to form a paste which is to be used for the next resist printing. A

resist of gum Arabic and lime is also printed at the same time. This combined

phase is known as gach. To shield the clay from smudging, saw dust or finely

ground cow dung is spread on the printed portion. After this stage, the cloth

is dried naturally for about 7-10 days.

Indigo dyeing: The fabric is dyed

in indigo. Next, it is kept in the sun to dry and then is dyed again in indigo

twice to coat it uniformly.

Vichcharnu: The fabric is washed

thoroughly to remove all the resist print and extra dye.

Rang: Next the fabric is put to

boil with alizarin, i.e. synthetic madder in order to impart a bright shining

red colour to alum residue portion. Alum works as a mordant to fix the red

colour. The grey areas from the black printing steps turn into a deeper hue.

For other colours, the fabric is boiled with a different dye. Madder root

imparts an orange colour, henna adds a light yellowish green colour, and

rhubarb root gives a faint brownish colour.

In ajrakh printing, the fabric is

first printed with a resist paste and then it is dyed. This process is repeated

several times with different kinds of dyes with the aim of achieving the final

design in the deep blue and red shade. This process consumes a lot of time. The

longer the time span before commencing the next stage, the more rich and

vibrant the final print becomes. Hence, this process can consume up to two

weeks, and consequently results in the formation of exquisitely beautiful and

captivating designs of the ajrakh.

The role

of the industries

Water plays a significant role in

ajrakh printing. Craftsmen treat the fabric with mordants, dyes, oils, etc.

Water impacts everything from the shades and hues of the colours themselves to

the success or failure of the complete process. The iron content in water is

the decisive factor which determines the quality of the final product.

Dhamadka was the chief location of

ajrakh printing for a considerable span of time due to the favourable source of

water. But after the 2001 earthquake, the iron content in water increased

heavily and the water turned to be unusable. Thus, the artisans from Dhamadka

village shifted to a new base and named it Ajrakhpur. They have taken

initiative in harvesting water keeping in view the fragile eco-system.

Ajrakh printing in Sindh, Kutch

and Barmer, are almost similar in terms of production technique, motifs and use

of colours. This is due to the fact that craftsmen in these areas descend from

the same caste-families of the Khatri community who migrated to Kutch and

Barmer from Sindh in the 16th century, and who are the descendents of the Indus

Valley Civilisation. At present, the Khatri families are distinguished for

carrying on with the traditional technique of ajrakh printing.

This Khatri community had been

involved in ajrakh printing in the village of Dhamadka long before the

destructive earthquake of 2001. All Ajrakh printers were shifted to the new

village of Ajrakhpur, which was set up primarily to commemorate the art of

Ajrakh printing and its highly proficient artisans. It is chiefly the Khatris

who have acquired perfection in this craft, and are carrying on the legacy of

traditional technique of their ancestors.

A

plethora of problems

Ajrakh craftsperson's today face a

number of problems, which hinder work.

Use of synthetic dyes and

sophisticated machinery: Use of eco-friendly and synthetic dyes and

sophisticated machinery which has lessened production time to a great extent is

proving to be a threat to the age-old traditions of this textile art.

Government loans: It is cumbersome

for artisans to get government loans which in turn discourage them from setting

up their own printing units.

High cost of blocks: The high cost

of wooden blocks used in Ajrakh printing imposes a great financial burden on

artisans as one block costs as much as Rs 3,000.

Crunch of water resources: There

is lack of water resources which is a mandatory criterion for ajrakh printing

in and around printing hubs.

Lack of new craftspersons: Due to

the lack of payback and great labour requirement, the upcoming generation is

hesitant in adopting this craft as chief occupation.

Traditionally,

vegetable dyes were used by ajrakh printers, but soon they began to use

naphthol dyes and synthetic dyes realising that vegetable dyes were proving to

be too expensive. But with the revival of the craft once again, ajrakh printers

have reverted to the use of natural dyes. New motifs are being added to the

design library day by day. Earlier, the body and the border used to be same,

but now complementary borders are in vogue.

Earlier, blocks used to be made in

a place called Pethapur. Now, blocks are made in the homes with the help of

machine-like drills. And, instead of natural water resources, modern printers

use water from borewells. The craftspeople are also planning to establish a

treatment plant for treating polluted water. Changing times have called for

critical changes both in terms of utility and design. But the beauty of the

traditional art has withstood the test of time. A number of hubs of ajrakh

printing have cropped up across India as well as Pakistan proving that art is supreme

and it transcends national boundaries.

In tune

with changing times

A number of NGOs are currently

engaged in making efforts to uplift this craft by providing new inputs to the

craftspeople. The NGOs conduct year-long training programmes to train aspiring

craftsperson in all relevant aspects of the art and give them monetary support

during the same. NGOs also back them in selling their products in the market

and earn due profits. But the number of such NGOs is not sufficient in

proportion to the number of craftspeople needing this assistance. Thus, the

government, the NGOs and those who are devoted to this craft should come

forward and devise ways and means to shield the interest of craftsmen who have

been nurturing this art for ages.

In spite of environmental

calamities, industrialisation and changing political regimes, the traditional

craft of ajrakh has survived. Craftspersons are revitalising the age-old use of

natural dyes for western markets. The handmade, ecofriendly and natural dyes

are preferred to non-eco-friendly machine-made and artificial dyes and colours.

With passage of time, ajrakh printers are now open to trying out new motifs, designs, dyes, materials and want to keep pace with the growing and changing contemporary world of fashion. At present, the printing art is being impacted by market demand and the new crop of ajrakh printers are prepared to accept and experiment with new pattern inputs provided by fashion designers. Hence, it has received a new lease of recognition both nationally as well as internationally. There is hope that these are not just transient fashion trends and that the ajrakh artisans will carry on the tradition of catering to the world with a fascination for highly proficient, elaborate, handcrafted textiles for generations to come.

Comments