For centuries, India artisans have been job workers for others. Thier talents have been used by top designers in the country and around the world without due credit. The payments have always been negligible, even though they are the main stars of many haute couture collections at fashion weeks. Meher Castelino writes about an initiative that is slowly transforming artisans into designers.

There are numerous non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in India and abroad who aid Indian artisans in selling their products, but none have been able to turn the artisans into businesses or brands.

This was what Somaiya Kala Vidya (SKV) sought to change when it stepped in to turn artisans into businesspeople who would brand their craft and create a label. Started by Judy Frater, known for her work in the field of crafts for over 20 years in Kutch, SKV's vision and purpose is quite clear. Its mission is to develop a new approach to design education based on existing traditions.

The core concept is that tradition is more than technique; it comprises concept and knowledge as well. SKV works within traditions, by understanding and drawing from their salient features. The focus of education is on acquiring knowledge and skills that enable artisans to use design effectively in their work, in order to successfully reach new markets, while at the same time strengthening traditional identity.

With its comprehensive one-year course, SKV works with artisans through a sustained, long-term, coherent programme. The aim is to work in the local language and environment, and integrate concepts and execution in tradition-based crafts. The goals are to enable artisans significantly improve their standard of living, and socio-cultural and economic status; strengthen the vitality and viability of the crafts in the national and international markets; to raise the level of education in the crafts sector; and to provide a successful example of educational reform.

"SKV also works with artisans in establishing and articulating what they already know, and how they traditionally work. In affirming this and building upon it, we identify the most effective path to our subsequent goals. SKV has established an approach of respect, sharing, and mutual teaching and learning. As much as possible, education is imparted utilising traditional methods," states Frater.

Course Correction

In 2014, SKV launched two new courses and an outreach programme. Business and Management for Artisans, a postgraduate course for artisan design graduates, is the first business course expressly for artisans. It teaches artisans to produce collections, as well hold an exhibition in a major city. Craft traditions for non-artisans aim to raise awareness and value for traditional arts and artisans.

SKV enables artisans to increase their incomes without necessarily increasing the cost of time and raw materials. Intrinsic to this goal, SKV understands what was traditionally created as art. All courses are hands-on. They are for practicing craftspeople, and focused on preparing them for the marketplace. The six courses build upon each other, and work towards creating a final collection that will be displayed and evaluated by a jury of market experts, and available for sale at a public mela. All courses can avail of SKV's computer centre, digital cameras, scanner, printer, and relevant collections. With the assistance of SKV staff, students are able to document and archive their work throughout the year.

SKV enables artisans to increase their incomes without necessarily increasing the cost of time and raw materials. Intrinsic to this goal, SKV understands what was traditionally created as art. All courses are hands-on. They are for practicing craftspeople, and focused on preparing them for the marketplace. The six courses build upon each other, and work towards creating a final collection that will be displayed and evaluated by a jury of market experts, and available for sale at a public mela. All courses can avail of SKV's computer centre, digital cameras, scanner, printer, and relevant collections. With the assistance of SKV staff, students are able to document and archive their work throughout the year.

The six courses comprise the following:

-

Session 1 is on colour/sourcing from heritage and nature where colour interaction, proportion, use of nature, emotional context of colour and defining unique selling points of their crafts are taught in the context of similar work done locally and nationally.

-

Session 2 is on basic design/sourcing from heritage and nature where the artisans look beyond focus on technique to see the bigger picture of aesthetics, define their unique selling proposition (USP) in the craft, basic design principles like contrast, balance, texture, emphasis, etc, and use nature/heritage as inspiration and abstraction of forms.

-

Session 3 handles market orientation/concept/costing where the artisans understand the variety of customers and different ways of segmenting market, understanding the relationship and difference between cost and value. They also learn about the flexibility in market demand, awareness of personal expenses, total products rather than just the craftsmanship competition, collection USP, as well as customer care and ethical behaviour.

-

Session 4 is about concept/communication/projects/sampling with trend forecast, abstraction, collection and USP being important.

-

Session 5 explores collection development/finishing where value addition, quality, collection USP, brand identity and relationship of materials to product are taught.

-

Session 6 is devoted to merchandising and presentation, which reviews all previous courses along with visual merchandising, value of presentation, importance of editing and collection.

The first batch graduated in 2014. The third class of 2017 had ten artisans whose work was evaluated in Gandhidham over a two-day jury assessment in August. The jury comprised Karishma Shahani Khan, fashion designer; Wasim Khan, design expert; Prof. (Dr) Anjoli Karolia, head, department of clothing and textiles, faculty of family and community sciences, Maharaja Sayajirao University (MSU); and Meher Castelino, fashion consultant and journalist. Four weavers, three ajrakh printers and three bandhani craftsmen presented their work for the four awards that were given after the two-day deliberation.

The Ajrakh Graduates

Amir Jusab Khatri's grandfather Gulmohamadbhai was a natural dye ajrakh printer in Dhamadka. His father continued the tradition, and Amir's elder brother runs a workshop and a shop, Gamthi Print, in the village. They also sell their fabric in Ahmedabad. Amir studied in Dudhai but did not enjoy it; so, after the tenth standard he joined the family business. He learnt block printing from his father, and has now begun to learn natural dyeing. Amir feels that ajrakh is his livelihood, and his heritage is a gift of god.

A good artisan, he says, creates new designs for the market, and a name for himself. A good design is one that remains popular. Amir dreams of taking his tradition forward and wants to expand the family business. He hopes that he can make designs of lasting popularity. Amir learnt to communicate through his work. From the Spring-Summer 2018 LA Colours Trend forecast, he selected 'Jardin de Plantes'.

Amir named his theme 'Nature: the New Future'. He printed in actual size to understand proportion and scale. He worked with Yash of MSU to develop layouts and prototypes for pants, skirts, stoles and dupattas, and created a collection of pants, stoles and dupattas, using his colour palette for fun new textured blocks and zany layouts. On the other hand, Khalid Usman Khatri's family was from Rapar. His father Usman moved to Dhamadka, where he printed ajrakh. By the time Khalid was born, his father had moved to Bhuj and established a screen-printing workshop, and later a handprint workshop. Usman slowly became well known. Khalid, meanwhile, went to a government school till fifth standard, then a madrasa near Bharuch for two years, and finished in the eighth standard. He learnt printing at 15, and worked with his father for ten years.

Usman died in the earthquake of 2001, and the business was destroyed. When Ajrakhpur was established, Khalid moved with his family to the new village and worked there, earning?100 a day. Once he was able to build his own workshop, he did job work. But his son Mustafa wanted to start his own work. He studied at SKV in 2015. After that, they established their business, and have been getting orders for a year now.

Usman died in the earthquake of 2001, and the business was destroyed. When Ajrakhpur was established, Khalid moved with his family to the new village and worked there, earning?100 a day. Once he was able to build his own workshop, he did job work. But his son Mustafa wanted to start his own work. He studied at SKV in 2015. After that, they established their business, and have been getting orders for a year now.

"Ajrakh was our livelihood," Khalid says. "But now it is our identity. That is how we have gone ahead. Talent is hereditary. I inherited my father's talent; and now I see it in my son. I am only interested in ajrakh. The future of ajrakh is 100 per cent good," asserts Khalid, who pays his own workers well. Everyone needs to move ahead," he says. "I like to teach them since information is to be shared." But, Khalid wanted to do something new. He saw his son studying at SKV and liked the way it opened up his mind. "During my own childhood, I didn't understand the use of studies," he recollects. "Now, I do. Artisans don't know their capacity. At SKV, their minds open up, and they can do new work."

Khalid had no dreams; he did not have goals either. But now, he does. "I want to do something unique and be known." At SKV, he expects to learn as much as possible, to take it all in. "The classes challenged me. When I look at a film song now, I am looking at colours! I could never draw, but now I can suddenly do! It makes me happy. I can bring it into my work. I saw paintings everywhere. Wall hangings can be a new product. I learnt how to get design ideas from experience."

From the Spring-Summer 2018 LA Colours Trend forecast, he selected 'Along the Bosporus'. He explored Bhuj palaces and sampled to evoke his theme. Khalid renamed his theme 'Anekta ma Ekta' which means "unity in diversity". He made a theme board, a colour palette and samples. Khalid experimented in creating and using the colours of his theme. Choosing appropriate motifs, using texture contrast and relevant principles of design he made stoles, dupattas, and a wall hanging.

The third from the group, Akram Jusab Khatri, is someone whose grandfather made red and black sadla in Vagad. When he passed away, the family moved to Dhamadka. Jusab did labour printing for one Anwar Isa. After some time he and his elder brother started their own workshop, printing red-black-and-white fabrics in natural dyes for the urban market outside of Kutch. Around 1997, Jusab closed the workshop and started a cloth shop. Soon, he moved on to wholesale marketing.

The third from the group, Akram Jusab Khatri, is someone whose grandfather made red and black sadla in Vagad. When he passed away, the family moved to Dhamadka. Jusab did labour printing for one Anwar Isa. After some time he and his elder brother started their own workshop, printing red-black-and-white fabrics in natural dyes for the urban market outside of Kutch. Around 1997, Jusab closed the workshop and started a cloth shop. Soon, he moved on to wholesale marketing.

Akram was two at the time of the 2001 earthquake. He lost a sister, and the family rebuilt their home. Two of Akram's uncles moved to Ajrakhpur, but Jusab remained. He was able to expand his shop, and called his business Akram Dyeing. Akram, the eldest of four brothers and three surviving sisters, studied till the eleventh standard. While in his last year of school, he learnt block printing and dyeing. A year ago, he and a partner started a workshop, with guidance from his father and SKV graduate Aslam. The family owns many blocks, but Akram ordered new ones in traditional patterns when he began the SKV course.

Akram feels that the future of ajrakh is good. "Natural block prints are in demand, and when one thing goes out of style, another comes in. But competition is growing." So, he wanted to learn design at SKV. "New things are usually accepted," he says. "Ajrakh is surely a livelihood," Akram feels. "But it is more too. It is my tradition. I dream of becoming a good designer and a good businessman. Both are needed."

Akram explored a range of markets in Ahmedabad and analysed market segments. He selected the SS 2018 trend, 'Jardin de Plantes', and named his theme 'Mine of Nature' or 'Nature's Bounty'. Akram learned finishing techniques, and worked with Bhumika from MSU to develop layouts for saris, stoles and dupattas. He even printed one layout in actual size to understand proportion and scale.

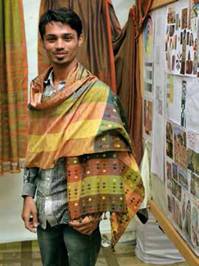

The Weaver Graduates

Dilip Dahyalal Kudecha's father studied in Bhujodi and learnt traditional weaving there. Since childhood, Dilip was interested in weaving and learnt the craft on his toy loom, fashioned out of nails and acrylic yarn. He wanted to experiment, and remembers that he wove his name in one sample. When Dilip was in the eighth standard, he would practice on the family loom in the afternoons when those were idle. He learnt extra weft from his mother. Dilip is a B Com graduate. His father wanted him to study further, but he wanted to weave. "If I want another degree, I can always do an online course," he says.

Dilip Dahyalal Kudecha's father studied in Bhujodi and learnt traditional weaving there. Since childhood, Dilip was interested in weaving and learnt the craft on his toy loom, fashioned out of nails and acrylic yarn. He wanted to experiment, and remembers that he wove his name in one sample. When Dilip was in the eighth standard, he would practice on the family loom in the afternoons when those were idle. He learnt extra weft from his mother. Dilip is a B Com graduate. His father wanted him to study further, but he wanted to weave. "If I want another degree, I can always do an online course," he says.

Dilip has been weaving part-time for five years and full time for three. He likes to do new designs. If he has trouble working a concept out, he asks his father to help. His father advises verbally, not with drawings; they even do this over the phone. "Weaving is identity and livelihood," Dilip says. "Our Kutch weaving is like handwriting. All of us sell in an exhibition because we each have a unique look.We mostly do traditional designs, but play with colour. Traditional work is again in demand. It is the effect of popular films. The Rann Utsav also brings tourists to Bhujodi," says Dilip.

He likes challenges, and wants to take weaving forward. "I am the new generation. I can bring that perspective. My father can bring balance. I will do something new, as much as I can in SKV. Then I will join my father. I wanted to do what I don't do at home. My favourite part was weaving. I saw how I could apply principles. I saw how people use products, and how stores display. In one craft there were many price and product ranges. We need to know about customers to present to them effectively."

Dilip renamed his theme 'Golden Time'. For his collection called 'Golden Age', Dilip created stoles, saris and dupattas, using his colour palette, zari yarns, and different techniques to merge colours.

In case of Mitesh Manji Sanjot, his father wove for twenty years in Kotai. He made shawls in acrylic and wool for Vishramji Valji in Bhujodi. Two years ago, he left weaving to work in Dena Bank in Lodai. Mitesh studied till the seventh standard in Kotai and from eighth to tenth in Swaminarayan Gurukul in Bhujodi. He did not enjoy school, but was interested in weaving which he learnt from his father four years ago. For the past six months he has done job work weaving for his uncle, Dayabhai.

In case of Mitesh Manji Sanjot, his father wove for twenty years in Kotai. He made shawls in acrylic and wool for Vishramji Valji in Bhujodi. Two years ago, he left weaving to work in Dena Bank in Lodai. Mitesh studied till the seventh standard in Kotai and from eighth to tenth in Swaminarayan Gurukul in Bhujodi. He did not enjoy school, but was interested in weaving which he learnt from his father four years ago. For the past six months he has done job work weaving for his uncle, Dayabhai.

Mitesh feels weaving is a means to creating an identity. "A good artisan concentrates on his work, creates well-finished marketable products and always innovates," he says. Mitesh dreamt of making a unique identity in the market and creating his own business. He hopes SKV will launch him on that trajectory. "I didn't know about balance, and other principles. I'll try them in weaving." Mitesh renamed his theme 'Nature is Gold'. He made stoles, dupattas, and a curtain after learning finishing techniques, and worked with Bhumika to develop layouts for stoles, dupattas and a sari.

For Pratap Nanji Kharet, his grandfather was the only weaver in Bandra village. He made shoes, and wove as well. When Pratap's father Nanji, the eldest of five children, was six, the family moved to Bhujodi. Vishramji Valji, his grandmother's brother, gave them a place to live. Nanjibhai married at 14 and wove satrangis for Devji, his wife's brother, and then for Vishramji. With Vishramji's support, he was able to start his own work in 1993. In 2003, Nanji got the President's award for a shawl, which took nine months to weave. Pratap's uncle, mother and grandfather have also received awards. As they lived in a large joint family, the awards provided important opportunities for exhibitions and international travel.

Pratap studied till the twelfth standard in Bhujodi. He did two years of B Com, but he wasn't serious in continuing. Pratap has accompanied his father to exhibitions all over India, and likes selling and dealing with people. In 2016, when the family was divided, Pratap mulled over about his future. He learnt weaving only six months ago from his elder brother, and today feels that handloom has a good market. "It is unlimited," he says. He recalls his grandmother's words; 'God gave us the job of making cloth so we should do it.' "Weaving is our heritage," he adds.

Pratap studied till the twelfth standard in Bhujodi. He did two years of B Com, but he wasn't serious in continuing. Pratap has accompanied his father to exhibitions all over India, and likes selling and dealing with people. In 2016, when the family was divided, Pratap mulled over about his future. He learnt weaving only six months ago from his elder brother, and today feels that handloom has a good market. "It is unlimited," he says. He recalls his grandmother's words; 'God gave us the job of making cloth so we should do it.' "Weaving is our heritage," he adds.

Pratap realised that he hadn't grown for some years. He was impressed with the change he saw in his friend Pravin; so he decided to study at SKV. "My father had struggled," he says. "I want to maintain his work and his name. I liked the practical exercises at SKV. This was the first time I did motifs like this." Pratap learnt to communicate through his work. From the SS 2018 LA Colours Trend forecast, he selected 'Casa Amarelo' and named his theme 'Art of Nature'.

The great grandfather of the fourth person in the group, Shamji Dhanji Mangariya, was a weaver. They belonged to Vadva Hothi, and wove plain white cloth for Rabaris and Ahirs. In 1995, members of their community had an altercation with Rajputs in the village and they moved to Bhujodi. Shamji's father began doing his own work, and selling to Khatris who had shops in Anjar. At the time of the 2001 earthquake, they were settled but lost everything; so they began working for Vishramji. Shamji learned weaving when he was in the seventh standard, by watching his father; he would sit at the loom during the weavers' lunch break. After the earthquake, he left school and began to weave full time. After working for Vishramji for 11 years, he wanted to create something new. He put up another loom, and worked overtime. He gave Nanji 100 stoles, which were a sell-out.

"Weaving is good work," Shamji says. "You do it at home. You can't do it alone-only if you have good family relations. Powerloom is fast but not creative; handloom lasts. It is so old; I believe it will go on into the future." Shamji wants to grow from his efforts; he wants to go to exhibitions. "We enjoy when we put our heart into it. I believe I can do good designs," he says. Shamji put theory into practice, dyeing the colour wheel. "We wove guessing the effect. But if we do by scheme it will be good."

"Weaving is good work," Shamji says. "You do it at home. You can't do it alone-only if you have good family relations. Powerloom is fast but not creative; handloom lasts. It is so old; I believe it will go on into the future." Shamji wants to grow from his efforts; he wants to go to exhibitions. "We enjoy when we put our heart into it. I believe I can do good designs," he says. Shamji put theory into practice, dyeing the colour wheel. "We wove guessing the effect. But if we do by scheme it will be good."

Shamji learnt about costing and value. "If a plain weave shawl is ?1,700 in Ahmedabad, I think I can do something." From the Spring-Summer 2018 LA Colours Trend forecast, he selected 'Regal Safari'. He visited Bhuj for inspiration, and named his theme 'Rajvadi That' or 'Regal Pride'.

The Bandhej Graduates

The grandfather of Abdul Vahab Haiderali Khatri dyed dhabla and khathi in Nirona, and sold them to Maldharis in Khavda and Banni. In 1972, he came to Bhuj and did napthol dyeing and washing.

Slowly he started a Bandhani business. Vahab's father grew up with Bandhani. At 14, he started napthol bandhani in cotton as labour work for others. Two years later, he went to Mumbai and did carpentry for several years. He returned to Kutch, married, and in 2006 started his own bandhani company, making gaji silk and cotton satin dress materials, saris, and dupattas. He still does the pattern, white and yellow dots, and sells without dyeing the background colour to local shops, while he continues his carpentry business on the side. Vahab's father wanted him to be independent.

Vahab is the elder of two brothers.

Since the eleventh standard, he has learnt bandhani from his father and a friend. Vahab wanted to come to SKV, but his father wanted him to study. He did the first semester of B Com, sharing his time between college and dyeing, which he liked more. Now, he is experimenting with his own work. "A good artisan knows and teaches others and is not afraid of competition," he says. He sees a bright future for bandhani if artisans keep the tradition and innovate. "We should preserve our tradition," he says.

Since the eleventh standard, he has learnt bandhani from his father and a friend. Vahab wanted to come to SKV, but his father wanted him to study. He did the first semester of B Com, sharing his time between college and dyeing, which he liked more. Now, he is experimenting with his own work. "A good artisan knows and teaches others and is not afraid of competition," he says. He sees a bright future for bandhani if artisans keep the tradition and innovate. "We should preserve our tradition," he says.

From the Spring-Summer 2018 LA Colours Trend forecast, he selected 'Casa Amarelo' and named his theme 'Journey of Nature'. Vahab learnt finishing techniques, and worked with Bhumika. "I didn't know what a garment was! With co-design we share ideas and learn."

A slightly different story comes

from Zaeem Mustak Ahmad Khatri, whose grandfather owned a bandhani and fabric

business in Mandvi. Zaeem's father was educated, and became an officer in the

Gramin Bank. His uncle continued the business, making traditional bandhani for

the local market.

After graduating in 2012, Zaeem

worked as an engineer for four years; first at a petro-chemical company in

Bhachau, and then at a bromine company in the Rann. When Zaeem lived in

Nakhtrana, he didn't like either the location or the long hours. In February

2016, he left his job and returned to Mandvi. He worked with his elder brother,

who sells dyes, but he wanted to have his own business.

Zaeem's uncle Akhtar suggested

that there was a good market for traditional bandhani in gajji silk. Zaeem felt

bandhani required minimal investment, and he wouldn't have to learn so much

because bandhani was in his blood. He searched for artisans around Mandvi, and

learnt work from Akhtar for about 10 days. He finally started his bandhani

business in October 2016.

Zaeem feels that the

future of bandhani is good, if one innovates. Most Khatris get their work

printed by the same people; so those look similar. "A good artisan listens

to clients' feedback and experiments," he says. He knows that he has to

study colour, and learn more about products. "Bandhani is the past and the

future," Zaeems says. Now it is also the present, he feels as he dreams of

becoming a successful businessman, and travelling aboard. "I like balance,

texture, and emphasis. Emphasis was new for me. I had visited Ahmedabad, but

not these shops. Online business was new." From the SS 2018 LA Colours

Trend forecast, Zaeem selected 'Regal Safari' and called his theme 'Royal

Time'.

Zaeem feels that the

future of bandhani is good, if one innovates. Most Khatris get their work

printed by the same people; so those look similar. "A good artisan listens

to clients' feedback and experiments," he says. He knows that he has to

study colour, and learn more about products. "Bandhani is the past and the

future," Zaeems says. Now it is also the present, he feels as he dreams of

becoming a successful businessman, and travelling aboard. "I like balance,

texture, and emphasis. Emphasis was new for me. I had visited Ahmedabad, but

not these shops. Online business was new." From the SS 2018 LA Colours

Trend forecast, Zaeem selected 'Regal Safari' and called his theme 'Royal

Time'.

Hamza Hasan Khatri's family is

originally from Aral. Prior to 1965, his grandfather did ironing and dry

cleaning in Virani. Then he began to make wool bandhani. Hamza's father

separated from the family, and lived in Vithun. He went to Delhi from

1975-1980, where he printed fabrics. Then he returned to Vithun, where he did

wool bandhani. Hamza is the sixth of seven children. Over time the family began

to work with cotton bandhani, getting job work from Mandvi, and eight years ago

they started working in silk.

Four of the brothers

currently do bandhani job work in silk. Two years ago the family shifted to Bhuj

for their bandhani business. But Hamza's father still makes woollen ludis for

Rabaris, and he still takes the ludis from village to village in the

traditional way. Hamza did his B Com in 2014 at Bhuj. While studying, he also

worked with a chartered accountant to gain experience. He learnt dyeing from

his cousin purely out of interest. He has three years of experience in bandhani

and six months in dyeing.

Four of the brothers

currently do bandhani job work in silk. Two years ago the family shifted to Bhuj

for their bandhani business. But Hamza's father still makes woollen ludis for

Rabaris, and he still takes the ludis from village to village in the

traditional way. Hamza did his B Com in 2014 at Bhuj. While studying, he also

worked with a chartered accountant to gain experience. He learnt dyeing from

his cousin purely out of interest. He has three years of experience in bandhani

and six months in dyeing.

"Traditional designs are good. New ones are less appreciated. The future of bandhani depends on the individual. I've already learnt to do what I thought wasn't possible. Bandhani is livelihood, identity and a means to success. I like contrast, and colour schemes. I have learnt what design is. I learnt ways to make patterns. I like tessellation. At the Gandhi Ashram, I saw spinning for the first time. Also prices and revenues must be fair to both artisan and client." From the Spring-Summer 2018 LA Colours Trend forecast, Hamza selected 'Jardin de Plantes'. He worked with Kriti of MSU for 'Metamorphosis'.

Comments