The condition of the global economy, already in a slump, is set to worsen as the covid-19 outbreak sweeps across the world.

For many quarters on an end, global financial institutions have been forecasting slower growth than usual. The first of the morbid predictions this calendar year came in the second half of January just as the world’s business, economics and political elite headed for Davos in Switzerland to attend the annual World Economic Forum (WEF) summit. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) on January 20 said that the global economic outlook “remains sluggish” as it trimmed its growth forecasts for 2019 and 2020 to 2.9 per cent and 3.3 per cent respectively.

“The projected recovery for global growth remains uncertain. It continues to rely on recoveries in stressed and underperforming emerging market economies, as growth in advanced economies stabilises at close to current levels,” IMF chief economist Gita Gopinath said in a statement. But neither IMF nor its chief economist could have foreseen what would happen in only weeks.

While the Davos meet was on, China was already in the throes of an epidemic caused by a novel coronavirus, which was still perceived to be more of China’s problem than anyone else’s. But within 10 days of the IMF statement, the World Health Organization (WHO) had declared the coronavirus outbreak as a global emergency as the death toll in that country jumped to 170.

Since then, the world has changed. The WHO declared it a pandemic on March 11. The global toll (as this issue goes to the press) stands at over 37,000 (and climbing) with close to 800,000 confirmed cases (and increasing) worldwide. The disease is spreading like wildfire in the US and UK, and has already ravaged Italy, Spain, France and Iran. It is not even recession anymore; the global economy is in an ominous tailspin, even as many governments have been announcing relief packages.

Gloomy Forecasts

And, there have been the projections, with each forecast / prediction as baleful as the other. On March 27, the IMF admitted that the world was in the face of a devastating impact due to the coronavirus pandemic and had clearly entered a recession. “We have reassessed the prospects for growth for 2020 and 2021. It is now clear that we have entered a recession as bad or worse than in 2009. We do project recovery in 2021,” IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva told reporters after a meeting of governing body of the IMF, the International Monetary and Financial Committee.

The “recovery” bit came with a catch—the key to recovery in 2021, Georgieva said, is only if the international community succeeds in containing the virus everywhere and prevents liquidity problems from becoming a solvency issue. That optimism seems a far cry since even the best of scientific minds do not see a vaccine breakthrough a year from now. If economic recovery is to be linked to containment and obliteration of the coronavirus, then a recovery in 2021 is quite unlikely.

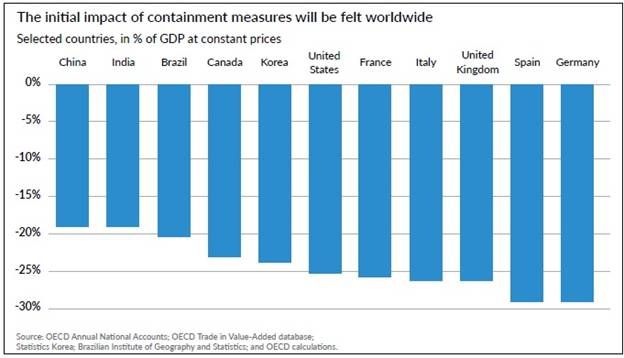

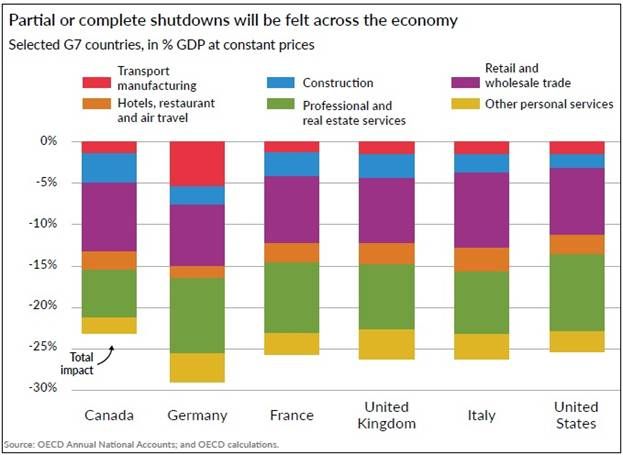

The same day, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released its latest estimates showing that the lockdown will directly affect sectors amounting to up to one-third of GDP in the major economies. For each month of containment, there will be a loss of 2 percentage points in annual GDP growth. Many economies will fall into recession. “This is unavoidable, as we need to continue fighting the pandemic, while at the same time putting all the efforts to be able to restore economic normality as fast as possible,” the organisation remarked.

OECD secretary-general Angel Gurr�a said: “The high costs that public health measures are imposing today are necessary to avoid much more tragic consequences and even worse impact on our economies tomorrow. Millions of deaths and collapsed health care systems will decimate us financially and as a society, so slowing this epidemic and saving human lives must be governments’ first priority. Our analysis further underpins the need for sharper action to absorb the shock, and a more coordinated response by governments to maintain a lifeline to people and a private sector that will emerge in a very fragile state when the health crisis is past.”

According to the OECD, “in all economies, the majority of this impact comes from the hit to output in retail and wholesale trade, and in professional and real estate services. There are notable cross-country differences in some sectors, with closures of transport, manufacturing relatively important in some countries, while the decline in tourist and leisure activities is relatively important in others. The impact effect of business closures could result in reductions of 15 per cent or more in the level of output throughout the advanced economies and major emerging-market economies. In the median economy, output would decline by 25 per cent.

“Variations in the impact effect across economies reflect differences in the composition of output. Many countries in which tourism is relatively important could potentially be affected more severely by shutdowns and limitations on travel. At the other extreme, countries with relatively sizeable agricultural and mining sectors, including oil production, may experience smaller initial effects from containment measures, although output will be subsequently hit by reduced global commodity demand.”

Global Response

The disease has been spreading fast, and the global economy is falling apart in trying to keep pace. On March 3, a good week before the WHO declared it a pandemic, the World Bank announced that it was making available an initial package of $12 billion in immediate support to assist countries coping with the health and economic impacts of the outbreak. The financing was designed to help member countries take effective action to respond to and, where possible, lessen the tragic impacts posed by covid-19. In just two weeks, the World Bank had to perforce revise the number as the toll kept spiralling. On March 17, the World Bank and IFC’s Boards of Directors approved an increased $14 billion package of fast-track financing to assist companies and countries in their efforts.

“It’s essential that we shorten the time to recovery. This package provides urgent support to businesses and their workers to reduce the financial and economic impact of the spread of covid-19,” said World Bank Group president David Malpass. “The Group is committed to a fast, flexible response based on the needs of developing countries. Support operations are already underway, and the expanded funding tools approved today will help sustain economies, companies and jobs.”

Just a day before the IMF’s gloomy prediction—on March 26—the G20 group of countries convened a virtual meeting to discuss the challenges posed by the pandemic and to forge a global coordinated response. The G20 group resolved to inject $5 trillion into the global economy to combat economic disruptions triggered by the covid-19 outbreak. The G20 grouping shares 80 per cent of world’s GDP and 60 per cent of world population and comprises India, the UK, US, China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Canada, France, Germany, Australia, European Union (EU), Japan, Indonesia, Italy, Mexico, Argentina, Republic of Korea, South Africa, Turkey and Brazil.

“We are strongly committed to presenting a united front against this common threat,” the leaders said in a joint statement after the summit. “We are injecting over $5 trillion into the global economy, as part of targeted fiscal policy, economic measures, and guarantee schemes to counteract the social, economic and financial impacts of the pandemic.”

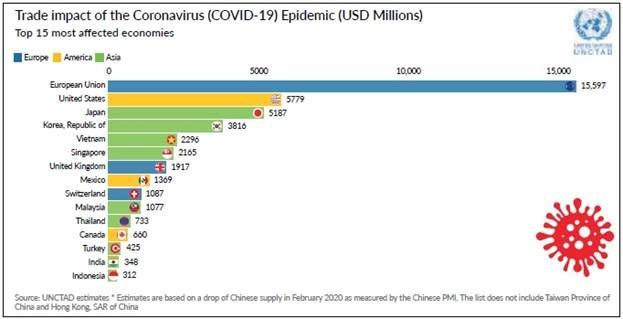

On March 30, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) quantified the package needed for developing economies: $2.5 trillion. The speed at which the economic shockwaves from the pandemic has hit developing countries is dramatic, even in comparison to the 2008 global financial crisis, the UNCTAD report said.

“The economic fallout from the shock is ongoing and increasingly difficult to predict, but there are clear indications that things will get much worse for developing economies before they get better,” UNCTAD secretary-general Mukhisa Kituyi commented.

The report showed that in the two months since the virus began spreading beyond China, developing countries had taken an enormous hit in terms of capital outflows, growing bond spreads, currency depreciations and lost export earnings, including from falling commodity prices and declining tourist revenues. On most of these measures the impact has cut deeper than in 2008. And with domestic economic activity now feeling the effects of the crisis, UNCTAD is not optimistic about the kind of rapid rebound witnessed in many developing countries between 2009 and 2010.

This article was first published in the April 2020 edition of the print magazine.

Comments