All stakeholders-governments, textile associations, investors, economists, researchers, designers- have to take responsibility. Or, the transition from linear to circular textile production cannot happen.

If you are a chemical engineer looking for a low-stress job in a quiet environment, by all means avoid research in chemical recycling of polymers. At least in Europe, this type of research has become a race.

Spurred by authorities, companies and ambitious institutes, researchers are supposed to work day and night in order to detect new ways for saving end-of-life polymer products like textiles, plastics, composites and coatings from incinerator or landfill, and for getting them a new life as a cost competitive, functional and environment-friendly recyclate.

On March 11, 2020, the European Commission adopted a new circular economy action plan with lots of measures for the entire life cycle of products. The plan clearly showed that the European Commission has high expectations from a range of actions in six economic sectors where circularity could have a bigger than average effect, including plastics and textile.

The Bureau of International Recycling (BIR), headquartered in Brussels (Belgium), which is the global federation of recycling industries with around 760 members worldwide, was very quick to welcome the EU’s support for recyclers as laid out in the new Circular Economy Action Plan.

The federation said it has no problem with the action plan that supports reuse above recycling. BIR remarked that for generations, certain of their members have collected goods for reuse, principally clothing, accessories and footwear.

Recycling is not new. It has been a common practice for most of human history. The great Greek philosopher Plato advocated recycling 24 centuries ago! In 1813, the British inventor Benjamin Law developed the process of turning rags into “shoddy” wool in the small town of Batley (Yorkshire). The shoddy industry lasted till at least the first World War. Also, chemical recycling of end-of-life polymers is not new. Chemists know for a long time that for some polymers, it is possible to convert them back into monomers. For example, PET can be treated with an alcohol and a catalyst to form a dialkyl terephthalate. The terephthalate diester can be used with ethylene glycol to form a new polyester polymer.

Cheap oil functions as a brake

Today, everybody agrees that the recycling of resources is a great idea; yes, a necessity and even a moral duty. How else then to explain that currently less than 5 per cent of the annual production of polymer products is transformed in to recyclates? Bob Vander Beke, manager - New Business Developments and top researcher at the Belgian institute of textile technology Centexbel, in Ghent, argues that the main reason is that the price of virgin polymers remains too low. In contrast, the selective collection and optimal sorting of end-of-life polymer products of which recyclates can be made is very costly. In addition, due to the complex composition of most discarded products, dissembling them is a daunting task.

Virgin polymers can be made of different feedstock: petroleum, natural gas, biomass, syngas, CO2. As long as the feedstock cost of monomers from which the petrochemical industry makes polymers remains low, the recycling of polymers cannot be advised as a commercially competitive activity.

When in early March 2020, Russia refused to agree with OPEC-leader Saudi Arabia on a production cut in order to increase oil export prices, the Brent global oil benchmark collapsed by 25 per cent, the sharpest decline since at least 1991. So, at present it does not look that high oil prices are around the corner. This is also bad news for the expected breakthrough of biopolymers. There’s much buzz around the rise of biopolymers. However, the annual production of bio-based plastics (including textile fibres) doesn’t exceed 8 million tonnes, or 2.1 per cent in comparison with the 380 million tonnes of fossil-based plastics.

In spite of low oil prices, the American consultant Nexant predicts that by 2035 Europe will already recycle 28 per cent of its discarded polymer products, much more than the US and the Gulf States of which the share of polymer recyclates is not expected to exceed 9 per cent.

Eco-design is a must

Textiles and apparel companies have many good reasons for bringing complex products to the market: functionalisation, product differentiation, hi-tech innovation, upmarket fashion trends. Great complex products, happy users! But wait, times are changing. When the end-of-life time of a complex product as arrived, you can no longer like in the past simply get rid of this product by casting it away.

Authorities and conscious consumers want circular solutions. So, probably some overstrained researchers will be ordered, in name of the circular economy, to look as quick as possible for a solution to recycle the wonderful complex product.

Is there no hope that soon a recycling genius will emerge, who like Archimedes in his bath, will get an aha-experience, and once for all will solve the whole recycling problem? Unfortunately not, since there’s not one problem to solve—there are thousands of them. Ingenious new insights and ‘green’ ideas can’t offer generally applicable solutions. It is because the diversity of polymer products, product compositions, additives, impurities and potentially applicable treatments and recycling techniques is too vast.

There is, however, one golden rule that in future should be applied to all complex textile products: take into account, already in the design phase of the product, that recycling will be part of its life cycle. ‘Eco-design’ is a must.

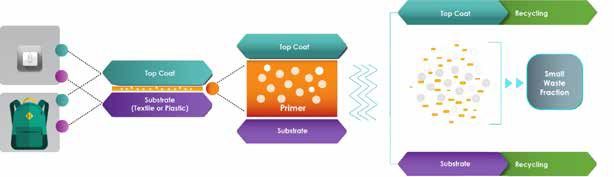

Centexbel is coordinating a European research project, called Decoat, aiming to promote eco-design in the development of coated and painted textile and plastic materials. Among the other participants in this project are the famous German research institute Fraunhofer, the leading Belgian supplier Devan Chemicals and Mercedes-Benz. The main goal of Decoat is to enable the recycling of textiles and plastic parts with multilayer coatings, which are typically not recyclable yet.

These ‘coatings’ comprise functional and performance coatings and paints as well as adhesion layers. Therefore, novel triggerable smart polymer material systems and the corresponding recycling processes will be developed. The triggerable solutions will be based on smart additives (like microcapsules or microwave triggered additives) for the ‘coating’ formulations and will be activated by a specific trigger (heat, humidity, microwave, chemicals). The Decoat consortium wants to start a pilot factory with a recycling line for coated and laminated parts and to organize demonstrations, especially of the debonding and recycling of outdoor materials like backpacks.

Upscaling is tough

It’s no surprise that the number of patents granted for recycling techniques and recycled products is growing. How much easier would it be for the textiles sector if mechanical recycling would suffice. However, in a modern textiles industry, mechanical recycling can only be a foreplay. At the end, most circular solutions will depend on chemical recycling. On paper, the task looks simple enough: break down discarded polymers to monomers or other start molecules and use them to make new polymers. Indeed, at the level of labs and pilot projects, successes abound. But Vander Beke warns: “The problem is that the upscaling to an industrial level that can be deemed profitable requires markets which do not yet exist.”

That doesn’t refrain clever people worldwide to feverishly continue their research work, especially in the difficult field of recycling blends. One of the most common blends, used in nearly all workwear and service textiles, is cotton / polyester. To enable chemical recycling of such textiles, cotton and polyester must first be separated. In 2014, a small team of researchers reported that they succeeded in the separation of polyester-cotton blends by using ionic liquids. By selective dissolution of the cotton component, the polyester component could be separated and recovered in high yield.

There’s actually no lack of techniques to break down discarded polymer products via solvolyse (like hydrolyse, glycolyse, methanolyse, ammonialyse, alcoholyse) or pirolyse (thermical decomposition).

In Europe, among the companies which successfully developed a chemical recycling method are the Italian Nylon6 manufacturer Aquafil and the Dutch firm Ioniqa Technologies. Aquafil has the knowhow to recuperate PA6-carpet yarn. The ECONYLyarn of Aquafil comes 100 per cent from Nylon6 waste.

Ioniqa is a clean-tech spinoff from the Eindhoven University of Technology, in the Netherlands, specialised in creating value out of PET waste. With a cost-effective depolymerisation process (using water or glycol), Ioniqa is able to transform all types and colours of PET waste into valuable resources to ‘virgin-quality’ new PET, which can be used for the manufacturing of new PET bottles, carpets or textiles. In 2019, the Dutch government recognised Ioniqa’s infinite PET upcycling technology as a major breakthrough innovation and announced Ioniqa as a winner of the National Icons Award.

Vander Beke regrets that the economic rentability of chemical recycling of polymers remains unclear and uncertain. He insists that governments, textile associations, investors, economists, researchers, designers—all of them—have to take responsibility. Otherwise, the quick transition from linear to circular textile production can’t happen. To the individual entrepreneur and researcher, who would think that his personal efforts are of little value, Bob says: “If you think that you are too little to have any influence, you probably have never spent the night in a room with only one mosquito."

This article was first published in the April 2020 edition of the print magazine.

_Big.jpg)

Comments