Banarasi saris came into being during the Mughal era. Their style and presentation have changed since then; they have been toned down to incorporate more neutral colours and minimalistic motifs.

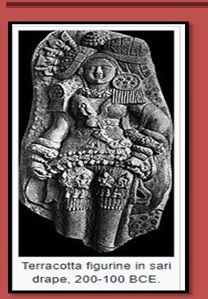

When a woman wears a sari, she epitomises Indian tradition. The attire brings with it a standardised code of conduct-the wearer's demeanour cannot be less than perfect, her gait as majestic as a ship at sea.

If just being arrayed in a sari can have such explications to it, then the six yards of this unstitched cloth has more to reveal than just clad the body. A blank canvas for the designer and the weaver, the sari comes alive with distinct artistic weaves, gold, silver embellishments and interesting prints. With numerous stories weaved into it-tales, motifs and colours, of fabric and art form, of its place of origin and worth-the sari has persisted and evolved through the ages. When we talk about the expression of a maker's artistic pursuit-a customised piece, and not mass produced, and hence not a stock reprint-we narrow down our subject to the traditional produces like the 'banarasi' sari here.

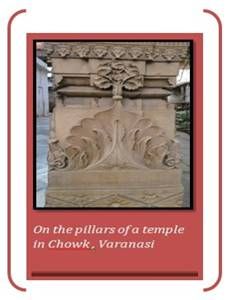

Crafts communicate the traditional and cultural heritage of a country. They outline the relationship of the present generation with the deities and shrines, nature, festivals and everyday life. There is a strong sense of continuity by inheritance. Some of the motifs and patterns of the banarasi sari are common to the walls and pillars of the ancient temples of Varanasi. Each region within India has its exceptional style, procedure of weaving and design that has been influenced by not only the geographical, social and cultural traditions but also by migrating ethnic groups. It was the Mughal era when banarasi saris came into being. Muslim artisans and craftsman chose Banaras as the city as it was rich in all aspects i.e, there were variety of techniques and processes that the city had already mastered by then.

Process of manufacturing: Weft & warp

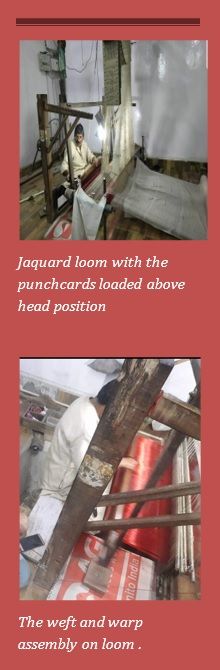

The 'naksha' technique of making brocade fabrics has been replaced by the jacquard attachment, though the rest of the technique has remained more or less the same i.e, throw shuttle pit looms and the extra weft (clockwise threads on a loom flanking warp threads) technique with twill weave is still practiced. Yarns have changed from pure gold or silver to imitation zari and silk has been replaced by synthetic yarns. Both traditional and contemporary designs are being used.

Algorithm of today's procedure practised by weavers:

-

Processed silk yarn procured from Gujarat and zari from Surat is segregated by fixing between the toes and segregated into spools of a particular breath.

-

A part of the yarn is wrapped and is multi-coloured as per the specifications of the designers.

-

Raw yarns are dipped in boiled colour solution for five minutes, and then dried by twisting in opposite direction between two poles. Once dyed it is washed with normal water and dried in shades at room temperature.

-

Warp is fixed to the warping machine and is reeled to the warp beam. The tautness of the warp is fixed by adjusting the levers of the loom.

-

Artisans check the tautness of the thread between the stretched warp and each thread is examined carefully. Finally yarns are stretched on iron rod and wrapped firmly to the beam.

-

Silk yarns are then transferred into small spools called bobbins with the help of spinning wheels. These bobbins are later inserted into fly shuttles while weaving.

-

Pure silver zaris are added to the sari. It can be tested by heating-if it melts completely then it is a pure zari or else it willturn into a chewing gum lump.

-

Banarasi saris are known for their gold and silver zari and finely woven with silk and decorated with intricate designs.Therefore, the next step is of pattern making.

-

Punch cards are made with cardboard sheets cut into required sizes. Design on saris is weaved using punch cards and these cards are the characteristics of jacquard looms.

-

The cards are punched according to the motifs so that they guide the thread through the loom.

-

Artisans load the punch card according to the design before weaving sari above head position; depending on the intricacy of the design a sari can take from a week to a month. Weavers use different colours of spindles according to the design and motif.

- The completion of sari is called reja pujna.

Waft & weft story: The term 'brocade' is derived from the Latin word brocare (to prick), which means needle work, loom embroidery or embroidery weaving. It is also known as 'kinkhab'-kin means golden, khab means dream-a fabric seldom or rarely seen in dreams or a golden dream. It is heavily woven with gold thread throughout. The traditional banarasi brocades were classified into three following groups viz zari brocades (kinkhab and baftas/poth-thans), amru brocades (silk patterns on silk, i.e., tanchoi) and abirawans (cut work brocades and tarbana). The gold and silver zari are used to generate gleaming embossed extra weft pattern that gives a classic touch to the sari.

Various types of zari

a) Pure zari: The central part of pure zari is made up of silk filaments, from which sericin has been removed. The silk yarn is twisted in red or yellow hues, over which thin wire (lametta) of silver and flatten wire (badla) is wound. The silver zari threads used in pure zari are electroplated with great expertise in pure gold solution to produce good quality gold zari.

b) Tested zari: Also available in the market as imitation zari because it has the external quality of real zari and therefore resembles real zari in terms of glimmer. This variety of zari is a bit inferior to the real zari because of the use of copper lametta instead of silver and silver embellishment is done on copper wire and to produce gold zari, the tested zari is embellished with gold solution.

c) Powder zari: The mechanised process followed for making powder zari is similar to the tested zari; it varies only where the powder gilding is done on imitation zari instead of gold electroplating.

d) Plastic zari: This is the most inferior type of zari where plastic thread is used as lametta instead of copper or silver.

Motifs used

There are umpteen motifs used. The design are of pretty floral pattern, vegetal designs, stylised dots, jal patterns, asharfi motifs, geometrical motifs, small flower (buti), mango motif (kalgha), human figures, bird depictions, animals and flourishing tree, all drawn from nature. Some of the motifs on the walls of the temples in Varanasi also find their presence on banarasi weaves.

Banaras silk sari is known for its softness, glimmer and luxurious look. The sari achieves a majestic look through its rich and intricate weave and zari work.

The variegated patterns

Brocade sari: The term brocade refers to those textiles where patterns are created by transfixing or thrusting the needle between thread patterns or the warp. The sari has multiple motifs in gold and silver threads, used as extra weft against silk background. The borders and pallav have scroll designs whereas the body of the sari can have several appealing patterns throughout as per the designer.

Chiffon jamdani: Unlike the other varieties of yarn in richer brocade saris, this kind has more coarse twisted yarns that form the warp sheet. The S and Z warped ends are alternately arranged that impart a wavy and crepe appearance to the textile. The jamdanis generally have buti patterns all over.

Jangla: These are a must have wedding trousseau item. These are rich and heavy due to the meena work jaal and jangla designs all over. The finish of the motifs is neat to resemble just the same on both sides of the fabric due to swivel weave without any floats. Jangla sari requires a minimum of two weavers who work together with 14 to 28 shuttles at a time.

Kora cutwork: In this kind, cut work are made against a plain ground. This gives a jamdani effect as the loose thread dangling between the motifs are trimmed manually and neatly.

Resham buti: An affluent kind of banarasi silk sari where butis are woven all over the ground bordered with heavy design and highly ornate pallav.

Satin border sari: This has pallav and border in satin weaves, the rest sari is plain.

Satin embossed sari: These have floral, ilayechi and charkhana patterns all over in satin weave.

Tanchoi: The motifs are woven in satin weave with silk as extra weft and are without zari. Its jamawar style and paisley motifs are thickly spread throughout. These are quite heavy.

Tissue sari: These have gold like appearance of cloth because they are woven with silk as warp and zari running as weft with combination of zari and silk in extra weft. Therefore, these are the most popular as wedding attire.

Protect weavers from commercialisation

Earlier scenario: Prior to independence, agriculture was thought to be the only instrument for rural development, but by the Eighth Five Year Plan, policymakers recognised small production units as a means to improve rural income by utilising the local human and material resources that could prevent migration from rural to urban areas. Many policies were introduced to promote handicrafts, of which handlooms formed a major part, but implementation of these plans could not be monitored effectively then to benefit craftsmen. The Uttar Pradesh Weavers Association has now bought the copyright to banarasi saris.

Path breaking: The National Handloom Day celebrations held at Banaras Hindu University in 2019 turned out to be a concerted effort to bring these behind-the-scene components of the handloom industry to the forefront. Several memoranda of understanding (MoUs) were signed by the textiles ministry.

Attempting to make a difference in the lives of weavers, the ministry teamed up with the National Institute of Open Schooling and the Indira Gandhi National Open University to ensure studying opportunities for weavers and their children. Under the artisans/children of artisans category, even NIFT provides admission to those candidates who have any one of their parent working under the development commissioner (handlooms) or the development commissioner (handicraft) of the ministry of textiles or the state government.

An understanding has been reached with the ministry of skill development under which weavers will be imparted skills like operating computers and English language. An MOU was signed with the Fashion Design Council of India under which leading fashion designers will work with handloom clusters and act as mentors to weaver service centres. A weaver helpline was launched, through which the weavers can directly register their problems. To ensure that the benefits trickle down to every weaver, a census of the weaver will be conducted.

To bridge the monetary constraints of weavers, the 'Hathkarga Samvardhan Sahayta Yojana' was launched under which weavers will be given 90 per cent of funds for maintenance and shifting of the looms. E-commerce is a formidable tool for promotion of handloom. Nearly 28 weaver centres across the country now act as collection centres for handloom products to be later displayed on e-commerce sites. These initiatives, if fully practiced and monitored well, will encourage weavers to continue despite all odds.

Metamorphosis of Banarasi

The grandeur of banarasi fabric craftsmanship is no more confined to the six yards of sheer elegance alone; its aesthetics is now being reflected in multiple dimensions.

Of late, through innovation, banarasi fabrics are being extensively used for ornamentation. Diversification in banarasi fabric has gone up. Banarasi brocade always enjoyed a special status in wedding apparel, but now it is being used in decor, potli-gifting bags, curtains, upholstery, brocade jewellery, highlighter cushion covers, table runners, drapes, creating ceiling, gift wrapping and wedding cards as well.

Designer Shruti Sancheti showcased her 'Kaashi to Kyoto' collection, which was iconic due to the introduction of Japanese contemporary motifs in banarasi fabrics.

In this age, any old craft has to fit into the modern lifestyle to survive. The aesthetics have changed; the lifestyle has changed; so the craft has to change accordingly. The basic soul of the craft remains the same, but in styling and way of presentation. it has to be contemporary. The colours have to be toned down; these have to be modified into neutral colours and more minimalistic motifs, quite contrary to bright colours used in banarasi fabrics. Banarasi also has a lot of scope in accessories like scarf but again it has to be muted and restrained to make it lucrative/acceptable for the foreign market. If the designers are able to achieve this and use banarasi craft in an optimum manner, it can make its presence felt all over the world.

Audio visual media, new methods of communication, developments in science and technology, flooding of the market with synthetic fabrics and intermingling of styles and culture are changing the traditional market for fabrics. Values too are changing from aesthetic endeavour to commercialisation that is leading to mass production and cheap imitations as markets have expanded. To keep the hearths burning and provide basic necessities to the weavers and their families, the traditional textile craft as a whole have had to make compromises and innovate to meet the changing demands for products of their looms, thereby preventing them from becoming extinct.

According to designer Ritu Kumar, change in yarn has led to banarasi saris becoming stiff and puffy. Over-designing of the fabric has also led to it losing favour with fitness-conscious youngsters, who do not prefer garments that give them a bloated look. Therefore, the need is to make it more attractive and glamorous for the market. No amount of subsidy from the government can make it fashionable; only quality handloom products can.

References:

1. www.khinkhwabs.com

2. Times of India articles

3. D’source

Comments