After UK's exit from EU, the country's most recent move in the global trade comes in the form of an accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) economic bloc, a free-trade agreement between 11 member countries covering the Pacific rim. So how is UK going to benefit out of this agreement? A detailed report.

It is almost raining trade deals in the past six or seven months for UK, as it races to forge trade relations with economies which were earlier trade partners through negotiations with the EU. UK's exit from EU, on the one hand leaves it with greater flexibility to decide on which countries it trades with more; it also makes it easier to negotiate terms that are favourable for the UK. The most recent development in UK's trade ambitions outside the usual EU partners is the accession negotiations with the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) economic bloc. This as per UK's International trade secretary Liz Struss "will allow them to shift the economic center of gravity from Europe to faster-growing parts of the world and deepen our access to massive consumer markets in the Asia-Pacific".

CPTPP is an inter-continental trade agreement, which had 11 members until now namely Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Mexico, Chile, Peru, Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam, Japan, Singapore and Vietnam. US withdrew from joining its predecessor, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017 and EU has also been never a part of this trading bloc, however there are only speculations that both might join the agreement in the future. Even without the large economies, CPTPP remains relevant as the member countries constitute almost 13.6 per cent of the global economy and 15.6 per cent of global exports, more than the export shares of US and China. The rules of the final agreement of CPTPP provides for almost complete liberalisation of tariffs among the members, only retaining tariffs in some highly sensitive sectors in respective countries. The rules of origin under CPTPP allows preferential treatment to a commodity only if 70 per cent comes from a combination of the CPTPP members.

UK's accession to the bloc will increase the relevance of CPTPP tremendously, while also providing a fillip to UK's trade flows post Brexit. Overall, the CPTPP economies exported goods worth close to $56.4 billion to UK in 2019 (8.1 per cent of UK's total imports), while they imported slightly more than $35.6 billion from UK (7.6 per cent of UK's total exports). EU and US remain UK's largest trading partners, although UK's accession to the CPTPP could soon bring some change in their shares. Within CPTPP bloc, Japan, Canada, Australia and Singapore are the largest trading partners for UK as they constituted 78.2 per cent of the CPTPP trade with UK in 2019. For UK as well, this will prove crucial for diversifying its trade and investment channels away from the European countries. The Pacific rim is expected to be the next high economic growth region going forward, and access to such markets could potentially create huge demand for UK's goods and services.

What makes CPTPP attractive?

For the UK, the agreement could have several measures that attract. Firstly, the fact that it represents a large economic bloc without China, US and any European nation participating. Secondly, just like the G20 (where US and China still dominate), CPTPP is a diverse set of advanced and emerging economies, which are increasingly becoming more relevant on the global stage. Thirdly, straight out of EU, UK desperately needs better trade ties with other economies. CPTPP also ensures a very high level of trade openness of the involved economies, which could provide UK the relevant market for its technology, digital services and financial services sectors. Also, having access to such a diverse set of economies and market structures could provide a much better integration of global supply chains and a much more efficient use of diverse resource endowments. The rules of origin requirements also imply that supply chains within this bloc could see much better development than achieved through bilateral deals.

Japan, Canada, Australia and Singapore are the more mature markets in the pack, contributing almost 61 per cent of the total exports from the bloc. Vietnam has been the growth leader with its vibrant and growing manufacturing sector, exporting 16 per cent of the total merchandise out of CPTPP members. A factor that makes this trade bloc very relevant in the recent times, is the absence of both China and the United States. While, both are large economies, their market powers are equally dominant. For the global supply chains to be truly diversified, it is important that trading blocs devoid of these market powers also develop significantly.

The agreement will also increase investments from the bloc to UK, as currently it constitutes almost 9 per cent of UK's investment outflows and 13 per cent of inflows. The deal is expected to increase the investments to and from this region greatly.

Gains expected for UK

There are however mixed views within the UK regarding the benefits out of this accession. A compelling argument supporting tremendous benefits to UK from CPTPP is based on the belief that the CPTPP economies are poised to grow much faster than EU and the former's trade relevance is also expected to increase much faster. Also, UK already has free trade agreements with many of the member economies of CPTPP and acceding to the agreement will only provide UK access to a set of very dynamic and thriving markets.

On the other hand, there are arguments which posit only marginal gains for the UK from this accession. One of the easy arguments against the 'large gains out of CPTPP' faction is that UK already has free-trade agreements with Japan, Canada, Australia, Singapore, Mexico, Vietnam and Peru and trade continuity agreement with Chile. This leaves additional gains from market access in Malaysia, New Zealand and Brunei, which are a very small fraction of UK's overall trade. This could limit the gains expected out of this accession. Also, there are serious concerns about the agreement affecting manufacturing and service sector jobs alike as greater cost competitiveness in markets like Vietnam and Malaysia, and increased migration from these countries could pose major threats.

The rules of origin feature of the trade agreement allow for cumulation of inputs for the purpose of tariff reduction. This could potentially be a source of gain for the UK as it provides greater flexibility to source inputs. However, UK imports a large part of its intermediate and capital goods from Europe, North America and China, discounting its expected gains from CPTPP rules of origin.

Also, the accession of UK into the agreement wouldn't mean any changes in the rules of the deal, as it is already in place. Some of the experts argue that for UK to bargain additional market access for its services in these countries would probably have been easier bilaterally. Singapore, Australia, Japan and Canada are the largest importers of UK services in CPTPP at present but UK services imports to these countries are still only marginal compared to their overall services imports. In the situation of bilateral deals already covering services trade, impact of accession to CPTPP could only be minimal.

Another argument is about UK's services exports to European countries being the largest and that distance between UK and CPTPP nations would keep benefits in services trade low. This contention however doesn't hold much value as US is the largest importer of UK's services. In the gravity models of trade, size of the trading partner matters as much as mutual distance, for trade to flourish between the two partners. Since, CPTPP in its totality represents one of the largest economic unit, the potential of services trade could be immense.

What's in it for textile sector trade

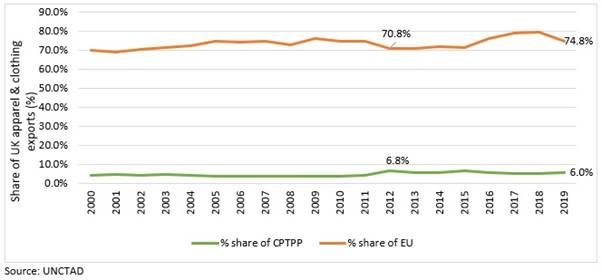

UK's textile sector was impacted tremendously from the pandemic, as demand collapsed, and many large apparel brands faced financial troubles. UK's apparel industry was largely dependent on exports to the European countries which accounted for as high as 79.1 per cent of UK's apparel and clothing exports for several years until recently. On the other hand, share of CPTPP economies has remained stagnant and has even fallen over the last decade (Figure 1). Lower trade barriers will probably lead to rise in UK's apparel exports to the CPTPP members, however distance will still play a large part in the cost of trade. However, it will enable larger investments in the textile and apparel sector from UK to other economies in the bloc. A shift from EU to a more diverse set of nations will make UK's sector less prone to country/region specific economic shocks.

Figure 1: Share of UK's apparel & clothing exports

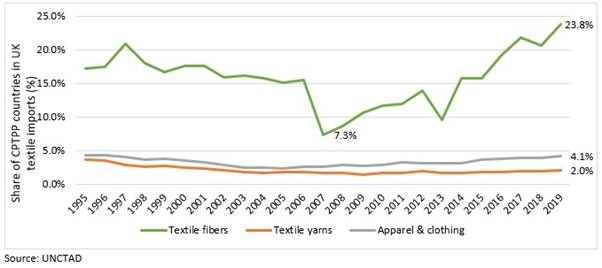

On the imports side, UK's textile related trade largely constitutes of apparel imports (more than 75 per cent, followed by made up articles (7.3 per cent), special textile yarn & fabric (close to 3.5 per cent) among other categories of textile yarn and fabrics. In all the major categories, imports from China dominate. CPTPP could possibly give tremendous push to CPTPP textile & apparel imports of UK.

Figure 2: Share of CPTPP countries in UKs textile imports

The rules of origin arrangement within CPTPP will also lead to a shift in sourcing patterns of these economies away from China. Vietnam largely sources its fabric from China, but the apparel so produced may not be eligible for duty-free access within CPTPP. For availing the benefits under the agreement, Vietnam will perhaps have to look for sources other than China for its apparel factories. It is still early to see which other country could serve as an alternative to China's scale and quality. Interestingly, Vietnam and Malaysia both depend heavily on China for its supply of raw materials, and both are part of CPTPP as well as RCEP, with China also present in the latter. Rules of origin arrangements are also present in the RCEP deal. How these differing trade deals will shape the global political and trade dynamics will be clear only with time.

UK is currently not a large market for Vietnam's apparel & clothing exports (merely 2.5 per cent of Vietnam's exports). But with both being part of this agreement and UK wanting a possibly shift from Chinese imports, tremendous opportunities lie ahead for textile flows between the two nations. UK and Vietnam also have a bilateral free-trade agreement, but the rules of origin requirements have 1) product specific rules of origin and 2) a de-minimis clause (maximum value of non-originating materials) which is more stringent than the minimum value of originating material (70 per cent) required in the CPTPP rules of origin. The UK-Vietnam FTA also recognises EU-originated goods as Vietnamese-originated or UK-originated. This could, in large part, restrict Vietnam's textile trade with China, as is the case with EU-Vietnam FTA. Not digressing much into these bilateral deals, the CPTPP has the potential to create more channels of economic ties and significantly boost textile trade between UK and the CPTPP nations.

Global textile trade was badly hit due to the pandemic. Revival of multilateralism through mutually beneficial trade agreements is being adopted to bring global trade back on track. CPTPP claims an important position in this regard as with UK joining, it will contribute 16 per cent to global GDP and 18 per cent of global exports. Whether other major economies like US, India, China and South Korea will join the agreement in the future is tough to say but UK's accession in the list provides a good signal for the global economy. That it is in the interest of even large economies to not sway towards protectionism. The benefits accruing to the UK will probably not be clear as bilateral FTAs will also have a role to play. But if it leads to a diversification of supply chains, in the textile sector particularly, it would achieve a tremendous feat for the global economy.

Comments