China’s recent five-year plan (FYP) provides direction to its economy through 2025. It largely follows the theme in Made in China 2025, aiming to make China the manufacturing powerhouse of the world. Focus on domestic consumption and strengthening domestic brands is a key highlight and will change China’s textile and apparel prospects tremendously.

History repeats itself. Economic, cultural and civilisational cycles abound in the world we know. Rise and fall of nation, states, fashions, fads and tastes and technologies are symbolic of this world that looks like changing but with very familiar patterns. The world economic order that we know today hasn’t always been like this and will probably change dramatically in the next few decades, maybe even sooner. It is perhaps a coincidence, that almost exactly 100 years apart, when the US gained economic supremacy in the 1910s, it is losing its economic edge to China. At least in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) terms, China’s GDP already surpassed that of United States by 2016, while nominally it may take only the next few years. China has made that intent clear in its recently released Five Year Plan (FYP) with less actual growth targets but more concrete objectives, mirroring somewhat the previous FYP but with greater thrust on market reforms, digitisation and industrial modernisation.1

China’s 14th Five-Year Plans (FYP) brings more perspective to how it positions itself over the medium as well the long term. It closely follows the Made in China 2025 plan released in 2015, as it focuses majorly on digitisation and rehauling China’s manufacturing to produce more high value-added products. The government also maintained close continuity between the previous and the current FYP, strengthening its focus on integrating China further into the global economy. For the very first time however, Chinese government has stayed away from defining a target growth for next five years in this FYP, likely because of tremendous uncertainties about global economy and China missing its growth target in the previous plan period.

China’s 14th Five-Year Plans (FYP) brings more perspective to how it positions itself over the medium as well the long term. It closely follows the Made in China 2025 plan released in 2015, as it focuses majorly on digitisation and rehauling China’s manufacturing to produce more high value-added products. The government also maintained close continuity between the previous and the current FYP, strengthening its focus on integrating China further into the global economy. For the very first time however, Chinese government has stayed away from defining a target growth for next five years in this FYP, likely because of tremendous uncertainties about global economy and China missing its growth target in the previous plan period.

As we had already noted in our previous article on Made in China 2025, the FYP plan outlined had very dramatic consequences for the global supply chains. China’s exports of high-value added manufacturing has increased sharply in the last few years while exports of more labour-intensive textile products and other low-value added products have seen only moderate growth. China’s race to make its manufacturing sector highly innovative and modernised is reflected partially by total stock of industrial robots in the country. Out of the overall global operational stock of industrial robots of 2.7 million units, China had the largest stock at 783,000 in 2019, with a 28.8 per cent share. China’s greater thrust on investments along the Belt and Road Initiative and dual approach of mixing relocation of industries with use of technology for low value-added sectors is an important feature of their development plan.

Important aspects of 14th FYP

1) Dual circulation strategy

While the US backlashed on China’s Made in China 2025 plan, the 14th FYP retains those aspects to a large extent. A big and new theme this time is the strategy of “dual circulation”, essentially putting more focus on “domestic circulation” of consumption rather than depending on “external circulation”. China would continue to favour boosting domestic consumption and rely less on external demand as the latter has become increasingly more uncertain. Private consumption and particularly household

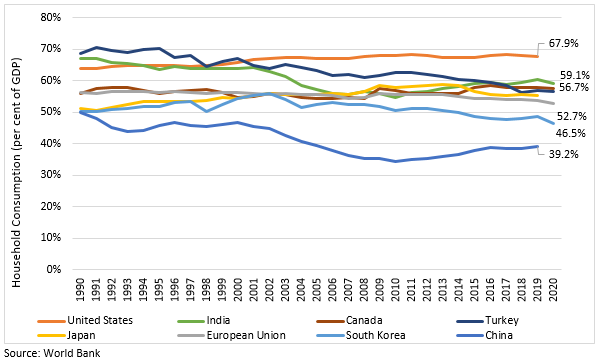

consumption in China has remained subdued over the years and remains one of the lowest among peer countries. Even while recovering from the economic shock of the pandemic, it was exports which helped Chinese economy more than the domestic demand. The current infrastructural demand is fueled by government spending and if not supported by simultaneous push to household consumption demand, could lead to further overcapacity in China and would again mean greater reliance on exports growth for sustaining industrial growth.

Figure 1: Household Consumption Expenditure (per cent of GDP)

2) Reducing regional disparity

A key feature of China’s development process until now is the regional disparity in terms of labour mobility, access to both financial and human capital, and overall development. The disparate growth prospects of the provinces in China are determined by factors such as cost of labour and capital, availability of high-quality labour, proximity to coastal areas and level of manufacturing activity. Even more problematic has been the vast differences in the debt levels of provinces and regions in China. Due to the pandemic, debt levels and disparities are expected to become even more stark.2 The recent FYP projects a long-term goal (2035) to increase China’s per capital GDP to levels achieved by developed economies and aims to bring more equitable distribution of economic growth across its regions.

3) Reforms in state owned enterprises

Chinese economic machinery has a disproportionately important role played by the state-owned enterprises (SOEs). SOEs are generally understood to be providing public goods with relatively much

lower operational efficiency than the private sector. Chinese SOEs are the largest globally in terms of assets and second largest in terms of revenue only after the US. Their participation in the Chinese economy is mammoth as well. In 2020, total revenue of Chinese SOEs was USD 9.8 trillion, 62.6 per cent of GDP.3 However, profitability in Chinese SOEs is much lower than the private corporations. For instance, just looking at Chinese firms included in the Fortune Global 500 list,4 profit margin for SOEs stood at 3.5 per cent vs 7.0 per cent for private firms in the list. SOEs also have the largest share in corporate debt in China, making them increasingly requiring of government support. The 14th FYP in continuation with the previous plan aims to reform the SOEs to make them more efficient.

4) Reducing carbon footprint

The five-year plan highlights the urgency to make China a leader in new energy and reducing its carbon footprint. As per a report released by Rhodium Group in 2019, emissions by China exceeded those by all developed countries combined, contributing almost 27.0 per cent to total global net GHG emissions. China’s emissions5 were a quarter of the developed world in 1990s and have tripled over the last 30 years. The FYP mentions ambitious plans about new energy, new energy vehicles, green and environmentally friendly products, hydrogen energy and energy storage among other areas to reduce dependence on fossil fuels. However, the current FYP hinges more on “promoting clean and efficient use of coal” and not eliminating it completely. China plans to use emissions reduction technology in its new coal-fired power plants to lower their sulphur and particulate pollution.

Continued push to develop domestic clothing and textile brands

In this FYP, China continues its push for development of domestic brands in clothing and home textiles. The thrust on building Chinese brands began from the 12th FYP, and since then many brands have become mainstream names in the Chinese apparel/clothing sector. Recently, consumer preferences have also shifted more towards domestic brands on the back of increased tensions between western brands and Chinese authorities regarding use of Xinjiang cotton. Recent study by Nielsen showed that 68 per cent of the surveyed consumers in China preferred homegrown brands due to rising nationalist sentiment. Until very recently, Chinese clothing/apparel manufacturers were largely OEMs for western brands and now brands such as Li-Ning, Anta, Urban Revivo and others are seeing increasing demand. This squares perfectly with China’s focus on increasing domestic consumer demand and western countries decision to rely less on Chinese supply markets. EU in its recent strategy revealed its priorities to reduce dependence on China in many strategic sectors (China supplied 52 per cent of such imports to the EU).

Conclusion

China’s recent FYP continues its policy push towards a more innovative and modernised manufacturing sector relying heavily on domestic consumption demand and less on exports. It continues to maintain policy direction towards green energy and cleaner modes of transport, adding greater thrust on more equitable regional development and bridging the urban-rural divide. The five- year plan envisages a much more confident Chinese economy preparing to increase its per-capita income to developed economies’ level by 2035. Some of the changes are already visible starkly on all fronts. For instance, in the electric batteries market, one Chinese manufacturer (CATL) has 32.9 per cent market share, and second biggest Chinese company BYD has another 6.0 per cent share. China’s

robotics demand remains strong as highlighted earlier. Other changes might take their own time. China’s push towards an equitable society hinges largely on introducing methods to redistribute wealth. Tax on inheritance and wealth have long been considered but are now being discussed more formally as part of this policy but may take a while before it actually bears an impact assuming it does what it intends to do.

3 https://www.csis.org/blogs/trustee-china-hand/biggest-not-strongest-chinas-place-fortune-global-500

5 https://rhg.com/research/chinas-emissions-surpass-developed-countries/

Comments