Increasing consumer demand and intense competition in the textile industry led to search for lower costs and so, higher volumes of cheaper articles and lower lifespan of products. But this strategy has led to tremendous waste and exploitation of resources and workers. Are textile producing countries responding well to reverse this trend? An analysis.

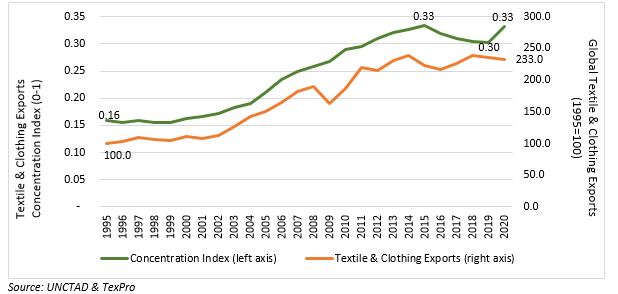

Globally, textile and clothing sector is one of the largest segments of economy, contributing almost $2.4 trillion to manufacturing and employing close to 300 million people across the world. Textile and clothing is also one of the most labour intensive industry and has had a large impact from globalisation over the last three decades. One of the characteristic changes that relates to its labour intensiveness is the level of concentration among the countries today. Data from United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) shows that concentration index1 for textiles & clothing exports has more than doubled in the last 25 years. This trend matches well with more than doubling of value of global exports of textiles & clothing.

Figure 1: Textile concentration index and textile & clothing exports

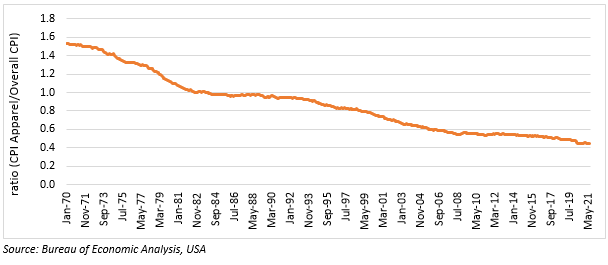

This is not new, and nothing is known about the underlying market structure which is more skewed towards countries with cheap and abundant labour. Although quality of the product plays a big role, price points are a significant determinant of clothing demand. The stickiness of apparel prices is starkly visible in apparel consumption prices, e.g Consumer Price Index (CPI) apparel in the US, which has historically grown rather moderately as compared to overall consumer prices in the US (figure 2).

Figure 2: Ratio of Apparel CPI and Overall CPI

The point of importance here is that global textile and clothing production has seen tremendous movement across countries in search of relative cost advantages. However, relentless scouting for cheaper ways to provide clothing has led to multiple issues which now pose tremendous threats to the sustainability of the industry as well as the ecosystem. Sustainability is a broad term involving economic, social and environmental factors, which are collectively also known as the triple bottom line. Sustainability issues in textile & clothing industry revolve around majorly three themes: 1) direct and indirect pollution of resources (environmental), 2) working conditions for factory workers (social) and 3) wages and contracts for workers (economic).

Context

Textile industry contributes close to 10.0 per cent of global GHG emissions and about 20 per cent of the global water pollution. This is only its direct impact. Since more than 50.0 per cent of fibre produced in the market is polyester, a large part of the clothing can’t be recycled entirely. Increasing consumer demand for apparel and brands’ inclination to rotate greater volumes (fast fashion) led to reduction in average lifecycle of a product. As a result, the amount of textile waste that is left to remain in the environment without proper disposal has become enormous. In the linear fashion model, it is estimated that more than 70.0 per cent2 of clothes end up in landfills and less than 1.0 per cent3 of clothes are recycled as clothing. Also, washing clothes made from synthetic material (polyester) releases 0.5 MT of microfibres every year into the environment, contributing 35.0 per cent to total primary microplastics released every year4.

This is the more visible environmental impact that this industry is infamous for. But several cases of poor working conditions and poor pay for the workers have also been highlighted over the years. Incidents like Rana Plaza in Bangladesh was drastic in its casualties and dramatic in its lessons, but not much has changed significantly to improve the way of functioning of the supply chain. In Bangladesh itself, the process to build mechanisms for responsibly auditing factories and safeguarding workers’ rights has been mired with politics and the core issue just hangs there as it is. In this note, we will take a closer look on the three themes of sustainability and how major hubs of textiles have moved the needle there. This to also to move beyond the usual debate about sustainability and textiles which mainly focuses on responsibility of brands leaving countries with limited role to play.

Broad indicators of sustainability

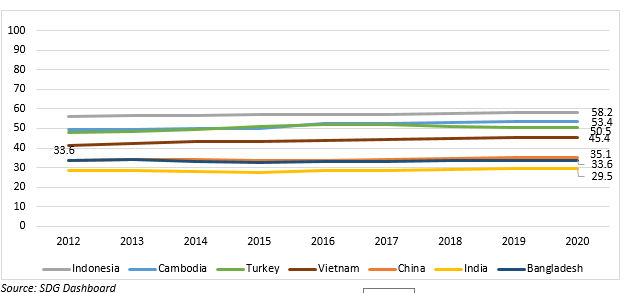

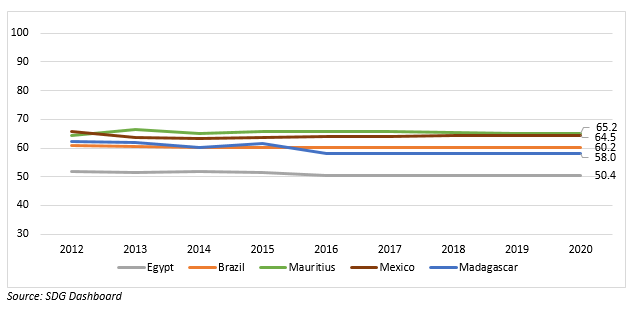

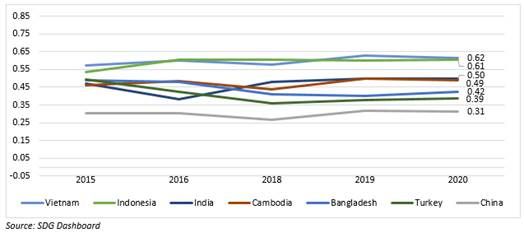

To begin with, some indicators that gives a general understanding about relevant countries are the global sustainable development sub-indices. Clean water sub-index in Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) ranks countries on marine water contamination due to chemicals, excessive nutrients, human pathogens and trash. Here the general picture is quite clear, all major textile producers are far from the best (100), and more significant ones such as China, Vietnam, Bangladesh, India fare worse than upcoming African locations (figures 3 & 4). However, conditions in the latter countries have also been deteriorating. This reflects a general lack of concerted effort to reduce pollution and waste from industries.

Figure 3: Clean Water Score (SDG sub-index) (Asian countries & Turkey)

Figure 4: Clean Water Score (SDG sub-index) (African countries & Mexico and Brazil)

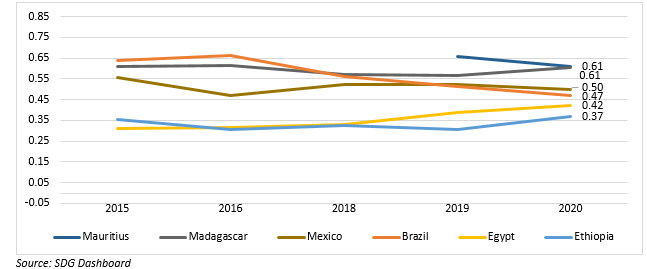

Another important index that reflects the social and economic aspect of sustainability is one related to labour rights enforcement (figures 5 & 6). Among the Asian textile hubs, Vietnam and Indonesia score the highest reflecting more favorable working environment for workers, while China, Bangladesh and Turkey fare much worse. The average however is much lower than the ideal score (0.85), and that will perhaps be slow to change as labour cost is still a significant factor in overall operational costs. African competitors also fare almost equally on labour rights, with Madagascar and Mauritius leading, while Ethiopia and Egypt being the worst performers. We will explore both the issues in much greater detail below focusing on several different aspects.

Figure 5: Enforcement of labour rights (Asian countries & Turkey)

Figure 6: Enforcement of labor rights (African countries & Mexico and Brazil)

Textile waste and circular economy

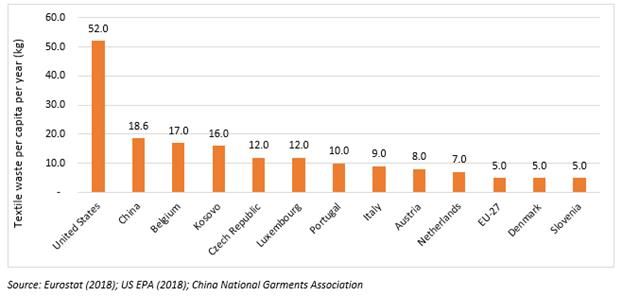

Textile waste maybe a small part of overall waste, it makes a large share of overall textile production as mentioned above. Figure 7 shows major economies, which are also large textile consumers, and their textile waste generated per capita. China generates the most textile waste at about 26 million tonnes per year, but in per capita terms is still behind the US. Figures for Vietnam and India are hard to come by as there are no official estimates. Bangladesh generates close to 577,000 tonnes of textile waste per year as estimated by industry reports. There are several solutions adopted to take care of such waste, most prominent of them being re-using clothes and textiles as they are (with partial or no processing), recycling to make textiles from scratch, incineration (combustion) and dumping in landfills. Re-using is the most common method adopted in all the countries and more common of the various ways is to export used textiles to other countries.

Figure 7: Textile waste per capita for select countries

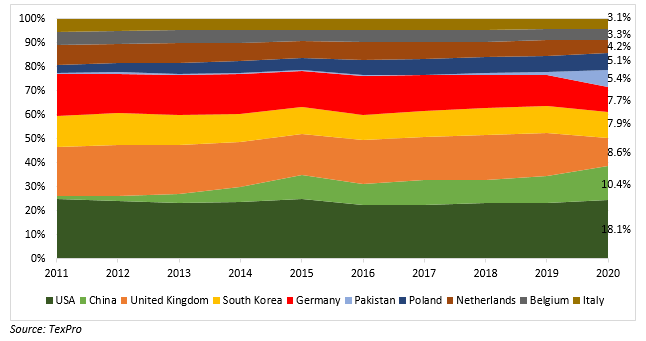

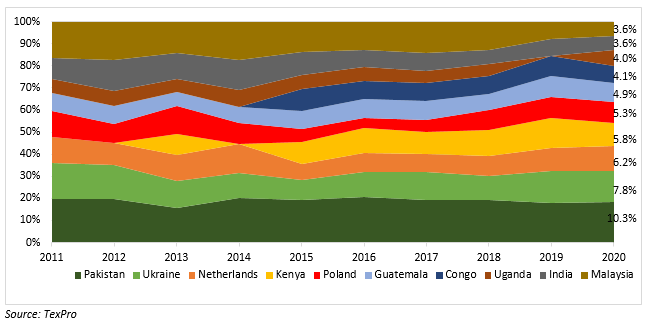

A large chunk of the textiles thrown away is sent abroad to less developed markets to be sold in the second-hand goods market. Global market for second-hand apparel & accessories is estimated to be $30-40 billion (BCG) and is expected to boom in the coming years. Global exports of used textiles in volume terms were as high as 58.6 per cent of total textile exports in 2014 and have since then moderated to less than 30.0 per cent as waste recycling capacity has increased in EU, China and the US. Although China has recently overtaken European countries exporting used textiles abroad, recycling of textile waste at home remains a large concern. Figures 8 & 9 show the share of exports and imports (respectively) of used textiles by country. While mostly all major economies in EU are large exporters, Netherlands and Poland are also dominant in sorting and re-exporting of used textiles, and therefore they also feature high on imports list. However, imports of used textiles are largely to African and Asian countries dominated by Pakistan and Ukraine. Amongst African nations, Kenya, Guatemala, Congo and Uganda are the largest importers. (Used textiles refers to goods under HS Code 6309)

Figure 8: Share in exports of used textiles

Figure 9: Share in imports of used textiles

While there has been a significant improvement in the way countries in EU and US collect and treat their textile waste, much remains to be done. However, few EU countries have been far ahead and are setting examples in building a circular economy for textiles. For instance, France has established an extended producer responsibility (EPR) system where brands are themselves held responsible for managing (collecting, sorting, recycling etc) textiles post-consumption. Sweden is also in the process to implement a similar policy. Other countries such as Netherlands, Germany, Finland and Denmark (covered in a recent study in 2020)5 are yet to establish such a policy and therefore, rely heavily on charitable organisations, municipalities to collect, sort and in some cases recycle waste. Within EU as well, the collection efficiency (collection as a share of consumption) differs widely (11-70 per cent)6 and much of it has to do with infrastructure (collection units density) and policy push to incentivise circular economy. Post collection treatment becomes lower even in the EU. For instance, it is estimated that proportion of garments reused in EU (which is safer than recycling) varies between 4-30 per cent, while less than 1 per cent of textile waste is recycled into fibres for new clothing and the rest in incinerated or landfilled. On the policy approach to waste management, France differs significantly from its neighbours as it has a separate circular economy strategy for textiles, which others are yet to put into place.

In the US as well, charities play a huge role in collection of used textile while other non-profit as well as for-profit organisations (including thrift stores) also play a crucial role as marketplace for collection/exchange of textile scrap or used textile. One estimate puts the size of thrift store industry in the US at $10.2 billion in 2019. Post collection, material is sent to sorter-graders which are generally private companies which either sort within US or send to other countries like India, Pakistan, UAE, Central and South America through their established networks. Post sorting/grading, material is sent for reusing as textiles and other uses. Secondary Market and Recycled Textiles (SMART) trade group report estimates that 45 per cent of material is sold for reuse, 30 per cent as institutional rag, 20 per cent into stuffing, shoddy and yarn fibre industry, and 5 per cent is unusable or unrecoverable due to spoilage7. While the process functions well, the amount going through this is still only 15 per cent of the total used textiles, whereas 85 per cent goes into the landfills. In the US, implementation of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is still under evaluation and could take some time to implement.

In China, the problem is even bigger. As we already know, China is the largest generator of textile solid waste while also heavily polluting its waters through release of chemicals from textile factories. China has only recently (in 2016) set out a plan to curb industrial wastewater release into water bodies and authorities in China have also been implementing fines on factories defaulting on pollution norms. In terms of recycling processes, China still lags far behind global best practices with only 15 per cent of the waste being reused or recycled. Although, last year, China announced an amendment in its Solid Waste Law which would set the tone for an EPR system, projecting to reach 50 per cent waste recycling by 2025. The plan is however envisaged for automobiles, electronics, lead acid batteries and packaging products right now and for textiles it might take longer.

Textile recycling and reuse in India also remains low at around 25 per cent, whereas the potential is more than 50 per cent. India is also one of the largest importers of used clothes, which are either sold in the second-hand market or recycled. Policy approach towards proper collection of used textiles/textile waste for reuse or recycling remains absent. The policy towards collecting and treatment of solid waste still largely revolves around dry or wet segregation and that is also lacking to a great extent in practice.

In Bangladesh as well, recycling of industrial textile waste for further production of finished products is taken up by several players but remains fragmented. Recently this year, around 30 fashion brands, manufacturers and recyclers came together to launch circular fashion partnership in Bangladesh with an endeavour to upscale its recycling capacity for textile waste and use it to produce new fashion products.

Similarly in Vietnam, large part of the solid waste currently goes to the landfills and hardly anything is reused/recycled. In the capital city of Ho Chi Minh itself, only 10 per cent of the solid waste is recycled currently. Recycling of textile waste is currently done by private players and no policy level frameworks are present.

In large part, collection of textile waste in Asian textile hubs lack streamlining and remains out of policy objectives, where currently the focus is more on reducing plastic waste. Used textiles is generally reused at household level or sent for recycling through informal channels but more prominently dumped in landfills.

This makes the situation even more desperate in the largest textile production hubs than countries where they are consumed. On the one hand, Asian and African countries have poor mechanisms to deal with increasing textile waste, and on the other hand, these countries import used textile from developed countries in ever increasing quantities, leading to further expansion of waste piles in these countries.

Social and economic factors

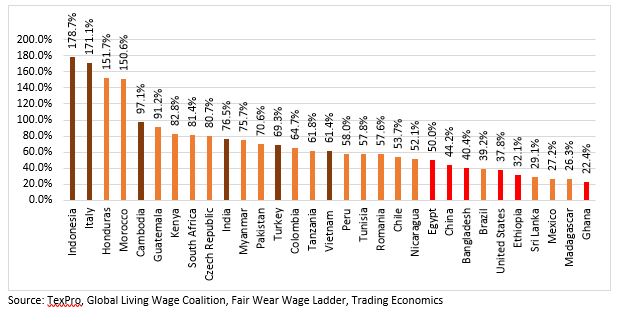

Now, let us come to the lesser talked about facets of sustainability. Countries with cheap and abundant labour pool have been attractive locations for manufacturing of textiles and have therefore been slow in changing labour regulations for better. Infamous incidents in textile factories in Bangladesh and Pakistan have brought to surface a key issue with the textile value chain: price competition thrives off minimal labour compensation and lower quality of working conditions. Even when working conditions become significantly better in richer western economies relative to Asia, workers’ wages remain a big issue. Some of the estimates put the share of wages to final price of garments as low as 4 per cent in Australia 11 or even lower for some apparel factories in the US12 . In several European countries, minimum wages for textiles are significantly lower than what will be considered a living wage, as reflected by a study by Clean Clothes Campaign13 . As per our internal comparative analysis (figure 10), minimum wage in textile sector is abysmally low in many countries as compared to the country’s living wage. Living wage is defined as the adequate monthly income required to cover the necessary living costs of an individual or a family. United States performs among the worst in our comparison basket, while Indonesia and Italy pay the best wages. Vietnam and Bangladesh which have proven their might in garments production recently, pay their workers only a fraction of the prevalent living wage.

While occupational hazard and safety concerns are less prevalent in the developed countries, they pose a double whammy in the developing textile hubs as workers work in exploitative conditions for a much lower pay relative to living costs.

The Better Work Initiative by the International Labor Organization tracks and provides more detailed updates on the working conditions in several developing countries. Its progress reports hint at gradual improvement in some while slower progress in other countries. Let us put down the work in some of the countries of our interest here. We discuss four Asian textile hubs below as more concise information is available for these.

1)Bangladesh

Bangladesh is an interesting case in point. While it attracted global attention due to its cost competitiveness, it simultaneously highlighted the much-ignored vices of the textiles industry until 2013. Although, Bangladesh’s relevance in the textile industry has increased even further as orders now shift from China as well, it’s working conditions, even when they’re improving, are not in focus. Better Work progress report 2019, shows that garment factories in Bangladesh have taken significant measures towards better work environment. Between 2015 and 2018, compliance rate of factories increased on factors such as storing chemicals and hazardous substances, readily accessible first-aid supplies at workplace, functioning safety committee, acceptable temperature and ventilation. Workers were reported to be working lesser number of hours on average from 9.14 in 2015 to 8.83 in 2018, and their earnings increased, while gender gap largely persisted. However, increasing proportion of workers were reported to be in better health than earlier14.

2) Vietnam

While its competitor trading nation has improved working conditions, particularly compliance on occupational safety, Vietnam maintains very high non-compliance, as per its Better Work progress report for 2019. Non-compliance rates for factories on worker protection, safety management systems, emergency preparedness and storing hazardous substances were reported to be as high as 93, 82, 74 and 68 per cent respectively. A large proportion of factories were also found in violation of the stipulated legal working time. However, the government has recently announced amendments to labour codes early this year to bridge the gap between domestic laboyr regulations and international labour standards, implementation will remain challenging15.

The report indicates general improvement in compliance with laboyr regulations, but much is needed to be done. For instance, there was absolute compliance when it came to forced labour and very high compliance rate on not employing child labour and non-discrimination based on several counts. However, compliance remained low on contracts and labour related indicators, occupational safety and health related indicators and working time related indicators. Although factories have improved compliance on allowing collective bargaining by workers, still 41 per cent failed to comply in the more recent round of surveys. This reflects our earlier interjection that labour regulations change, even though more swiftly on paper, but rather slowly on the factory floors.

3) Indonesia

As we saw in the previous sub-section, Indonesia pays the most appropriate wages to its workers, and its factories are also compliant on many of the factors considered by Better Work in 2018. Compliance rates are particularly high in areas related to abolishing forced and child labour, collective bargaining, while it was much lower in occupational safety and health, work time, social security & overtime wages, and work time limits16.

Compliance on occupational safety and health hazards were particularly low. 90 per cent of the factories were found in violation of the norms on providing health and first-aid services at workplaces and having safety management systems, while 85 and 80 per cent respectively were lacking on norms related to emergency preparedness and storing chemical and hazardous substances. After these, non-compliance was the highest on worker protection, social security benefits, contracting procedures and overtime respectively at 85, 76, 72 and 66 per cent. Better Work reports that non-compliance on overtime is mostly because of stiff competition with neighbouring exporters where legal working hours per week are at 48 compared with 40 in Indonesia, impacting factories’ working schedule there. An important facet highlighted in the report is that 42 per cent of the factories had company regulation which were not consistent with the latest labour laws and regulations, which was primarily due to: a) lack of information about any updates in labour laws and regulations and b) delay in implementing changes.

4) Cambodia

The last compliance review report for Cambodia was released in 2018 and it showed a general improvement in compliance rate from 33 per cent to 44 per cent since 2015. Compliance to providing for minimum wages was found to be high, while factories were slow to change when it came to providing for appropriate number of leaves. Compliance was also high on abolishment of child labour and forced labour, while there was heavy non-compliance recorded on mechanisms for employees to understand employment contracts, occupational safety and health norms, and worktime regulations17.

Major improvement was recorded for overall compliance, again particularly on factors related to child and forced labour and discrimination based on race, gender and other metrics, while registering very high non-compliance on factors related to paid leaves, an area where non-compliance increased over the years. Non-compliance was also high on contract related metrics specially on employers abiding by fixed-term contracts. On occupational safety and health metrics, non-compliance was particularly high on having health and first-aid services at workplace, having an appropriately lit workplace, properly labelling or storing hazardous substances, having acceptable ventilation and temperature and assessing potential hazards in the workplace.

For China, the analysis and understanding of labour conditions are somewhat anecdotal and recently much of the outrage against China’s textile industry has been because of broadly understood prevalence of forced labour in Xinjiang region, one of the largest cotton growing regions in the world. One of the reports by China Labor Watch (CLW), a non-profit organisation, covers extreme violation of labour regulations in some of the toy factories in China. Now, it’s not obvious to jump to a conclusion for the garment factories from this, however it will also be hard to assume that the conditions in one industry could be materially different from another, when both are highly labour intensive. The report by CLW highlights violations on all relevant metrics from proper living conditions, avoiding excessive overtime work to mistreatment at factories. However, the factories were reported to comply with minimum wage laws but they are usually much lower than living wages as seen in figure 10 above. China’s compliance to its own labor regulations lag significantly, and even more when it comes to international standards18.

In neighbouring India, working conditions for textile workers are equally grim. Fair Wear surveyed (2019) textiles factories in major hubs across the country and recorded broad violations on several metrics19. India still has a large percentage of child and forced labour, and forced labour is often implicit rather than through direct means. The report covered three locations – Delhi NCR, Bangalore and Tirupur in India, highlighting that the surveyed factories performed miserably on paying minimum wages, providing acceptable working and living conditions, having and upholding employee contracts and proper treatment of workers. Overall, prominent textile production hubs in India still lag miserably in establishing basic worker rights.

Similar conditions prevail broadly in textile sector in Pakistan, as reported by Human Rights Watch, an international non-profit organisation, highlighting violations on implementing regulations related to minimum wages, occupational safety and health, harassment at work and working conditions20.

One important facet of textile sectors in India and Pakistan is the large presence of informal sector and therefore lax regulatory oversight and implementation of policies, even when they are present on paper.

Conclusion

In the note we have attempted to analyse countries on metrics of sustainability. Some of the European countries such as France and Sweden are frontrunners in establishing circular economy for textile sectors while countries such as United States, China, and other Asian economies are much behind. Dealing with textile waste is going to become of greater concern with Asian and African countries, which lack resources to provide for proper infrastructure for circular economy.

On the social and economic factors all major textile producing economies have much to achieve. Worker pay remains significantly low even in some parts of developed world, while some Asian countries perform much better. However, on working conditions the latter have much to change. Bangladesh has seen major improvements recently, while Vietnam, Cambodia and Indonesia are catching up. China, for its scale, particularly remains a laggard in establishing proper working conditions and is now facing major backlash for it. India and Pakistan are also far away from being ideal nations either.

Comments