How many times have women struggled to fit into a garment of her usual size in a trial room? But then she tries on a different garment of the same size. And voila! It fits. She kind of liked the first garment. A larger size fits her too. But most likely, she will choose not to buy it because it has a size label that does not make her feel comfortable.

Social media has been a platform for venting out about the ways these situations play with the emotions of even the most practical and logical women. They tend to question their self-esteem and self-worth. And the practice of ‘vanity sizing’ has a lot to answer to these women.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines vanity sizing as “the practice of assigning smaller sizes to articles of manufactured clothing than is really the case, in order to encourage sales.” Also called by some as ‘insanity sizing’, it is the phenomenon of ready-to-wear clothing of the same nominal size becoming bigger in physical size over time.

Even with all the talk about body positivity and the rise of plus-size fashion, our culture is still obsessed with smaller sizes. The media constantly portrays the message that small and thin women are ‘beautiful’. From Disney princesses to runway models, this image is advertised over and over again. This has an even more enforcing impact on fashion. The way brands label larger cut pieces as a smaller number size to appease the customers into thinking that they are smaller messes up the body image issue (O’Connell, 2021).

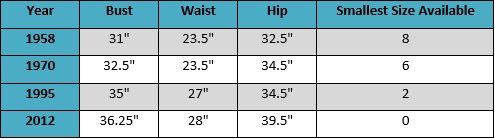

The origin of vanity sizing lies in the United States, with the American women getting bigger over the years. The original sizing system of 1958 was updated again and again until it was completely discarded in 1983. The result was that the manufacturers had the liberty to define their own sizes. Soon they began to size downwards to flatter the consumer. The chart given below shows, how the measurements for US Size 8 have changed over years (Dockterman, 2016).

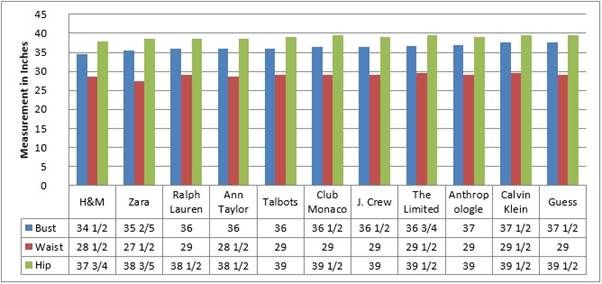

However, the confusion does not end here. Different brands use different measurement charts for their size labels. The graph below shows a comparison and disparity of Size 8 garment measurements across a few brands (Dockterman, 2016).

However, vanity-sizing is just not about making the sizes smaller. Brands such as Victoria’s Secret promote brassieres to make women feel they have bigger breasts. The brand makes its brassieres fit up to three sizes up than usual (Jilek, 2021).

How sizes change over time and brands is a facade to a deeper problem. It leads to an obsessive focus on numbers. Alexis Conason, a clinical psychologist and author of the book The Anti-Diet Plan has said, “Vanity sizing plays to our insecurities and manipulates us into buying clothing that we may not even like because the tag says a size smaller than you typically wear. When we equate sizing with self-worth, vanity sizing essentially allows us to buy a superficial dose of confidence. We think: I fit into a size 4, I AM good enough! But this is almost always short-lived because true self-esteem doesn’t come from a piece of fabric with a number on it.” (Igneri, 2017).

This issue can be devastating to people struggling with body confidence and eating disorders. Studies show that the constant expectation to fit into a specific size can trigger feelings of depression, anxiety and social withdrawal (Igneri, 2017).

It is evident that we are in a society where size matters. If it was not for the media preaching that thin is beautiful and beautiful is thin, women would not be scared of going up or down sizes. The fear that a larger size is not beautiful enough creates panic.

Dr. Cristina Castagnini, psychologist and certified eating disorder specialist, says, “The problem really is that our society is obsessed with one size only: thin. Only 5 per cent of the population naturally has this ‘ideal’ body size, so the 95 per cent of the population who don’t are left to feel inadequate and pressured to have that ‘ideal’ body from the cultural norms perpetuated in our society by the barrage of media and advertisements.” (Igneri, 2017)

The issue of vanity sizing is frustrating enough when customers try on the garments in stores. However, currently, clothes worth about $240 billion are purchased online each year. Studies show that 40 per cent of what consumers buy online is returned due to sizing issues (Dockterman, 2016).

However, some brands are making an effort to solve this issue. Rational Dress Society sells its jumpsuits in 248 different sizes. The sizes are derived from taking specific measurements and body types and instead of assigning a numeric size, their sizes are randomly named like ‘delta’, ‘alpha’, ‘buffy’, ‘tango’, etc. This model may not work for all fashion brands, yet this can change the way women feel about size labels and ease their anxiety (Rational Dress Society, 2022).

Machine learning algorithms are also explored by brands for providing sizing solutions to consumers. Online size advisors use machine learning to help shoppers with the right size garment. The algorithms use the information provided by the shopper and compare it to other shoppers purchasing similar items. The data is then aggregated and calculated into a ‘fit score’, and size recommendations are made.

A number of companies, such as True Fit, Le Tote, etc and designers like Melissa McCarthy are trying to push the boundaries of traditional sizing. Body Labs is creating 3D fit models for the consumers, Gwynnie Bee is offering subscription services for plus-size womenswear, while Fame & Partners is allowing consumers to customise their clothes.

But the question is whether these solutions will solve the issue. The main problem lies with how women feel about accepting a bigger size. Vanity sizing works because, deep down, all women are a little vain. So, the projection of ‘thin equating to beautiful’ needs to be changed, and the message of body positivity and self-love needs to be spread and incorporated into our everyday lives.

Comments