The single greatest cause of the logistics crisis has been poor management on the part of customers in all sectors of the economy who have unwittingly undermined the entire supply chain and in doing so made logistics more fragile. The problem began with globalisation.

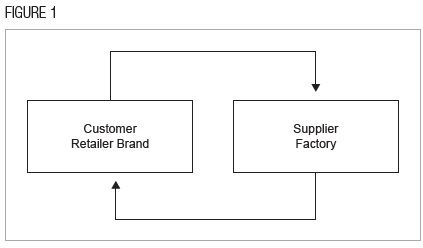

At the outset, globalisation was relatively simple and worked well. The customer would buy the garment from the factory, which would supply all the materials and production and ship the finished order to the customer (Figure 1).

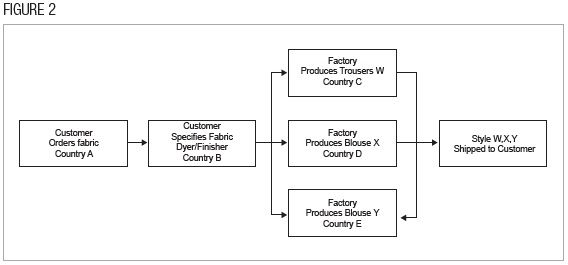

The process changed when the customer took over from the factory to source and negotiate the fabric and trim directly with the suppliers. This provided both lower cost and better-quality control. The customer could place the material order at one location and produce the garment orders, even in the case of matching coordinated garment sets, in many locations in different countries. This ensured that material colours would be uniform, while the garments would be produced in the factories of choice (with the lowest FOB cost) regardless of country (Figure 2).

Where once we were dealing with only two parties, we are now dealing with five suppliers located in five different countries, and because these are garment sets, we are hoping that everything will arrive at the store in the importing country simultaneously. This is indeed an enormous logistical stretch.

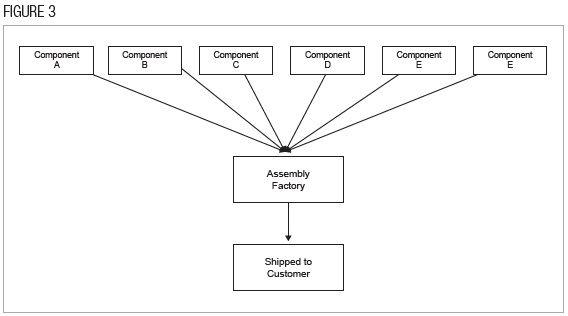

Sourcing hardgoods, such as computers, cell phones and automobiles became even more complex, as customers sourced components at different locations, often in different countries and moved the pieces to a central location for assembly (Figure 3). The problem is that if any single component arrives at the assembly factory late, the entire process is delayed.

Problems arising from multiple-component sourcing affect everyone, not only the US and the EU, but also China.

Just as logistics is becoming more complex, the suppliers at every stage are being pushed to move faster because at the end of the line we have the consumer who has been promised ever faster delivery. The retailer has created an environment of instantaneous gratification. Consumers have become addicted, demanding ever greater speed-to-market: “WHAT’S GOING ON? I ORDERED BY SUPER-DELUXE ULTRA-BAR-B-Q AT 9:30, IT IS NOW 11:00. MY GUESTS WILL BE ARRIVING IN LESS THAN AN HOUR. I WANT MY SUPER-DELUXE ULTRA-BAR-B-Q NOW!”

There is yet a third factor: Cost reduction. In the past logistics had buffers, such as built-in extra time and additional raw material inventory. All that has been taken away in the name of higher productivity and increased efficiency. The ship carrying 1,000 containers has been transmogrified 10-fold to become the ship carrying 10,000 containers, while the crew has been cut by two-thirds from 60 to 20. The result is greater and more serious errors, such a ship running aground stopping traffic in the Suez Canal or tankers creating serious oil spills.

The backlog of ships at the port of Los Angeles, causes delays in loading cargo in China, Vietnam and all the other garment exporting countries simply because the ships to be loaded are sitting idly queuing up to be unloaded in California.

Because logistics by its very nature is a multistep process where each step is carried out at a different location, solving the problem at one location simply moves the bottleneck down the line to the next location. As a result, operating the port of Los Angeles 24 hours a day, seven days a week, will result in trucks arriving at the closed warehouse at 3:00 a.m. Sunday morning.

The combination of greater complexity, faster movement and cost reduction has led to a classic example of BIRNBAUM’S PRINCIPLE OF COMPOUND MISTAKES:

• Every process is subject to mistakes. They may occur once every thousand, once in 10,000 or once in 1,000,0000 operations, but we must accept that mistakes are inevitable.

• As the process becomes increasingly complex, the propensity for mistakes increases. Where once mistakes increased arithmetically, they now increase geometrically.

• The need for continual cost-saving moves increases worker stress, with the result that the propensity for mistakes increases yet again. Where once mistakes increased arithmetically, then geometrically, they now increase exponentially.

What we have seen in the recent logistics crisis is simply the end of any exponential movement. We have reached the point where everything has become a mistake and the process has collapsed.

Going forward, we must make an effort to understand what will happen and more importantly, what we can do to create remedial strategies.

Regrettably, we do not yet have the necessary data.

First, the latest information (International Trade Centre) takes us only to December 31, 2021, before the onset of the logistic breakdown.

Second, we have little or no idea of how our customers are dealing with the logistics crisis. Changing sourcing strategies cannot be carried out overnight. Garment exporting countries and their factory suppliers will not be affected for at least a year.

However, there are areas to consider. Notably not all exporting countries will be equally affected.

For example, India has some real advantages when facing the logistics crisis.

1. Local textile industry: The country has almost total product autarky. From the raw cotton fibre to the finished fabric, the entire process is carried out in-country. Others may be adversely affected by the logistics crisis, but at least on the supply side, India’s factories can rest easy.

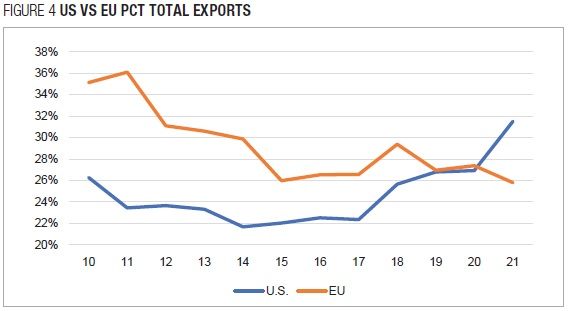

2. Less reliance on the big-two importers: As we can see from Figure 4, as of 2021 the US accounted for 31.5 per cent and the EU 25.8 per cent of India’s garment exports.

• The EU: While it is unfortunate that exports to the EU are declining, we have to accept that the EU has alternatives. They have a very large domestic garment industry as well as regional neighbours with growing garment exporting capabilities. India’s reliance on its EU customers has been steadily declining since 2011. The logistics crisis will at most accelerate the existing decline.

• The US: This is a different situation. Unlike the EU, the US has no domestic garment industry. Furthermore, unlike the EU, the US has few regional garment exporting neighbours. At best it can rely on only its Caribbean regional garment imports. Currently, CAFTA-DR accounts for only 10 per cent of US garment imports, leaving US retailers with very limited choices of where to go. At the end of the day, US imports from India may well increase.

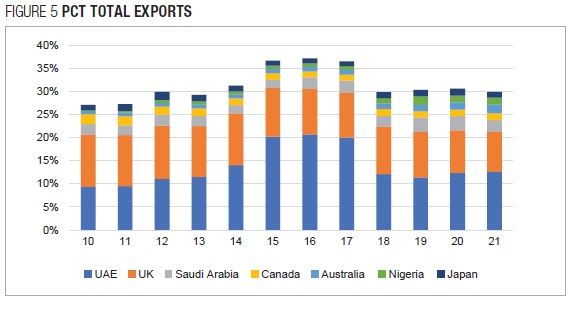

3. Diversified import customer base. Every garment exporting country talks about the need to diversify by adding customers in new importing countries. India is one of the very few success stories. As we can see from Figure 5, India’s second tier import customers account for a steady 30 per cent of its total garment exports. When we consider the geography, with the exception of the UK, India enjoys good proximity to its customers which will minimise the effects of the logistics crisis on exports to these countries.

What to do?

The global garment industry is about to undergo difficult times, with the logistics crisis being only one of the many challenges. Our industry is in the early stage of massive and fundamental changes, where the winners of the past will be the losers of tomorrow.

For countries such as India, the logistics crisis and other serious problems need not be obstacles but rather opportunities to move forward. India’s garment exporting industry might do well to concentrate its efforts on the seven, second tier import customers. They appear to be loyal. This is a time not just to solidify what you already have but to expand further.

New free trade agreements (FTAs) would be an important first step. India should go further to a create special relationship by creating a strategy for development. The strategy begins by working to define what India’s trade partners need and what steps India’s government and industry can take to meet those needs.

Comments