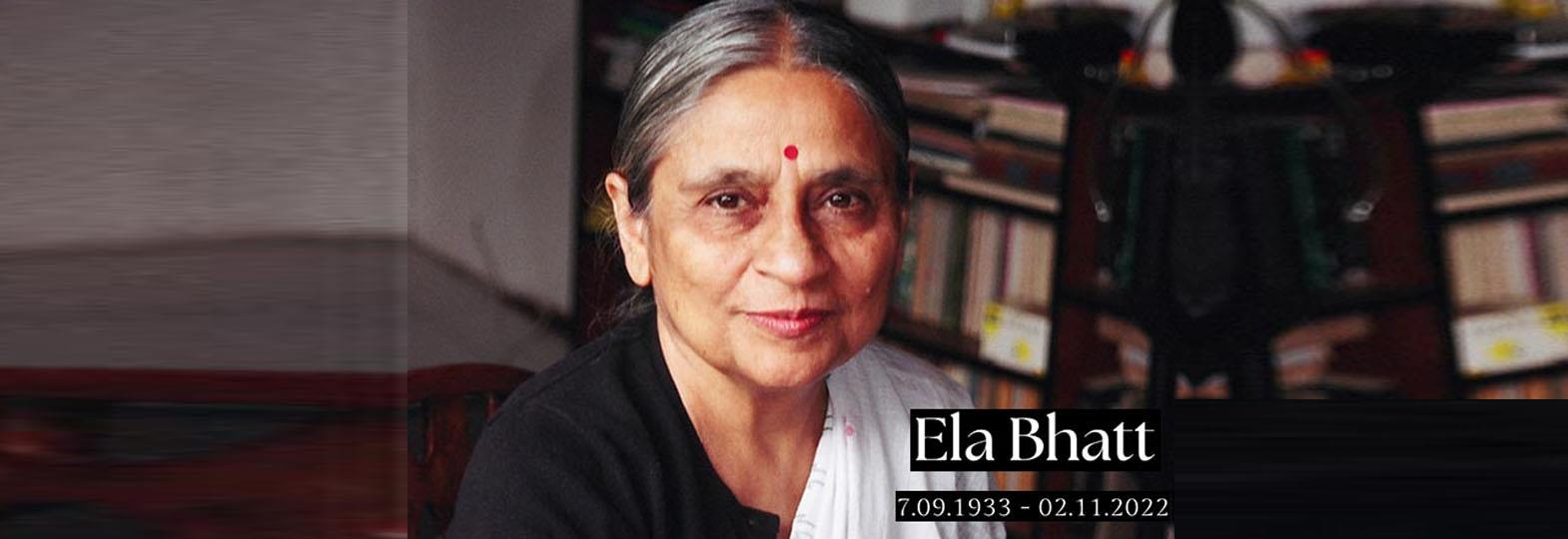

Who was the common thread of inspiration of famous designers Anita Dongre, Ritu Kumar, Archana Shah, crafts practitioner and activist Jaya Jaitley, and Dastkar founder Laila Tyabji? The person was none other than Ela Bhatt, the founder of the world’s largest informal organisation SEWA (Self Employed Women’s Association), the eighty-nine-year-old visionary, who died last month (November 2021). After the legendary Kamala Devi Chattopadhyay and Pupul Jayakar (founder of NIFT), she very successfully held the baton of empowering Indian women and giving them dignified lives through their crafts and skills through her organisation SEWA. Ela Bhatt’s life and SEWA are a huge knowledge repository for the good number of sustainable fashion and craft brands in India, which are today supporting artisans’ livelihood and trying to provide them with a decent income and with dignity. Let us identify what Indian sustainable fashion entrepreneurs can learn from Ela Bhatt and SEWA.

Bringing Professionalism to Skilled Artisanship: Embroidery is a great skill of Gujarati women. Ela Bhatt professionalised it through SEWA in the mid-seventies by forming a centre in Banaskantha in the northern part of Gujarat with the help of designer Ritu Kumar and Laila Tyabji. The centre converted natural embroidery skills of Gujarati women relatable to the growing Indian market of ready-to-wear and taught them to work with templates and paper patterns. SEWA set up Hansiba museum, managed and owned by artisans, to preserve and protect traditional embroidery done in Gujarat and Sindh from growing industrialisation. Sewa Kalakruti is a retail brand promoted by the Gujarat State Women’s SEWA Cooperative Federation. Its objective is to give the artisans an ideal business environment along with an interface via which they can directly market their products to customers. In Hansiba and Kalakruti, 65 per cent of Kalakruti’s revenue from products sold goes directly to the artisans. To motivate themselves, artisan women start their days in SEWA by singing the Hindi version of the American civil rights anthem ‘We shall overcome’. Similar organisations of SEWA were formed in various craft centres across India.

Flexibility: The organisers at SEWA are guided by “how to” principles rather than narrow “what to do” guidelines, which promote natural experimentation and innovation. Staff members and organisers commit to inquiry and fact-finding, and they value objectivity. Such flexibility helps SEWA to adapt and grow easily while keeping the principles of the organisation intact. This made SEWA a “learning organisation” long before this term came to management vocabulary. For this flexibility, SEWA never had an ideological backlog to get a grant from various sources. SEWA targeted funds from different state and central government projects, NGOs, and Corporate Social Responsibility and funds of various corporations. They made it very clear that as long they are committed to serving poor women for their income, livelihood, health, education and childcare and asset building, they should not have any ideological constraint to collect funds from different legitimate sources. With this flexibility, SEWA became very successful in different states where different political philosophies reined. SEWA took the opportunity of market economy and innovations in technology without losing its focus on giving dignified life and income opportunities to its members.

Artisans 360o Well-being: SEWA not only focuses on its artisan members’ incomes, but they also try to address the issues of health, education, childcare, banking, microfinance, and shelter for their proper well-being and dignity. For that reason, SEWA became a model of reference for development economists like Amartya Sen, and Jean Drez, world-class universities, Central and state governments, the World Bank, WHO, UNESCO and several other global institutions. Apart from many prestigious national and international awards, SEWA and Ela Bhatt were awarded the Right Livelihood Award, often referred to as the alternative Nobel Prize in 1984.

Associating Vision and Values in Day-to-day Operations: SEWA never forgot its vision and values while the organisation scaled up to become the world’s largest informal organisation. SEWA’s clarity on prioritising self-employed poor women’s well-being is reflected in its operations. Some of the principles from the Gandhian belief system that it follows include truth, non-violence, integrating all faiths and people, promoting local employment, and self-reliance. The culture and values of egalitarianism, inclusion and participation are promoted by addressing each other as “brother” or “sister”, conducting all meetings in a highly participatory manner, promoting multi-faith prayer, and not firing any SEWA staff member, but rather adjusting their work to match their talent. The highest-paid SEWA employee earns no more than a few times only that of the lowest-paid SEWA worker.

Ethical Leadership: Ela Bhatt, the founder of SEWA, created leaders at the grassroots of the organisation. Her vision, idealism, simple but dignified style of living and single purpose of helping poor women inspired a cadre of professional women to join and stay with SEWA. These professionals have in turn created a culture of participative management that reduced the social distance between managers and mentors. The “one term post” rule allows a regular rotation of officeholders and decentralisation of power. There is less chance of loss of continuity as the core management team is very stable. SEWA makes a conscious effort to develop new leaders from working women (Blaxall, 2004). These grass root level leaders and professional leaders enabled Ela Bhatt to serve in various national and global forums and organisations like the Rajya Sabha, Nelson Mandela-founded human rights and peace-promoting organisation Elderly, Women’s World Banking (WWB) – a global network of microfinance organisations, and adviser of World Bank. These, in turn, helped SEWA in brand building and organic growth.

Thinking and Acting Ahead of Time: From the sixties, Ela Bhatt started questioning the traditional trade unions as they could not organise informal workers like rag pickers, street hawkers, embroidery stitchers, vegetable vendors, push-cart operators because they do not have proper employers. Elaben (as she was fondly called) fought and won a legal battle, formed SEWA and became India’s largest trade union within a few years to protect the informal workers. SEWA negotiates with authorities in a larger space, on behalf of informal workers, even in the state itself. Apart from negotiation and collective bargaining, SEWA formed a sizable number of cooperatives like ragpickers cooperatives, embroidery artisans’ cooperatives, pushcart operators’ cooperatives and many more to create wealth for SEWA and serve the members of SEWA. SEWA was a pioneer in providing microfinance and banking facilities for its members through forming The Shri Mahila Sewa Sahakari Bank before Bangladeshi economist Mohammed Yunus conceptualised it and applied it in his Nobel Prize awarding project Gramin Bank. She supported the reservation system as it was helping her poor members of lower caste to win their struggle for livelihood. This decision delinked SEWA from her parent organisation – the Textile Labour Association formed by Mahatma Gandhi.

Ability to Work Successfully with Diverse Stakeholders: Like Gandhi or Nelson Mandela, Ela Bhat was respected by diverse stakeholders because she was ideology-neutral and intensely empathetic and humane. Her SEWA grew very successfully with diverse stakeholders like communities, governments, corporations, NGOs, educational institutes, foreign agencies etc. Gandhi once said, “I have neither read Smith, Mill or Marx. But when in doubt, a little voice tells me, neither look to the left or the right, but walk the narrow straight path.” Elaben trusted that straight path, with all stakeholders as fellow travellers.

Thus, Ela Bhatt’s life and journey provides huge learning opportunities to the big and small players of the Indian fashion and craft industry in terms of scaling up, generating livelihood for the artisans and keeping our age-old sustainable practices intact without shunning business ethics.

Comments