The ancient geographical area of Bengal in India was well known for its dexterity in textiles. This was due to the abundance and availability of cotton and silk across the region. Bengal became the centre of exchange of trade and culture of the subcontinent. The distinct pattern of weaves of Indian textiles was in high demand throughout the world.

The diversity in motifs, patterns and weaves of Indian textiles were further highlighted by the variations in the regional cultures. In Bengal, the range extended from finely weaved jamdani to the high thread count spun cotton muslin. However, it was the baluchari sarees that depicted the life of the rulers, affluent and traders.

Silk was available in abundance in the wet landscape of Bengal and Assam. Bombycidae and Saturniidae cocoons were available in plenty. The ancient texts of Arthashastra by Kautilya and Acharanga Sutra of Jainism mention silk weaving and the availability of silk in Bengal. Inscriptions in Sanchi Stupa also support these facts. Historical evidence suggests that silk weaving was highly organised, with different stages of production involving different castes. The weavers had a high status and were part of the Tanti community. According to the census report of 1891, approximately 1,34,000 acres of land spread across Birbhum, Bankura, Midnapore, Hooghly, Murshidabad, Rajshahi and Malda was used by over 90,000 cocoon cultivators.

In 1704, Murshid Quli Khan, the Governor of Bengal, shifted his capital from Dhaka to Makshudabad (current Murshidabad). The capital was located on the banks of the Bhagirathi river, thus giving it a strategic location advantage. The arrival and settlement of the Jain trading community from Gujarat, Marwar and Mewar also contributed to this decision.

Baluchari derives its name from Baluchar, meaning an island of sand. The origin of this craft lies in this island which was later submerged due to a flood, and the population was shifted to Murshidabad. Mulberry silk is primarily used in the making of baluchari. The process comprises multiple steps. Continuous filaments are drawn from the cocoons that become soft after boiling to make yarns. This process is called Khamru spinning. The leftover short fibres are twisted using the thumb and index fingers and called Matka spinning. The untwisted Khamru Silk makes the weft and extra weft. The twisted silk yarns are used for the warp, as these offer greater strength.

Degumming and bleaching are done before proceeding with the dyeing. Bleaching removes the natural yellow shade of the yarns and also makes it softer, shinier and lighter. The moist yarns are then dyed with natural colours. As per a study, 17 natural colours were obtained from natural dyes in Bengal. These included blue, red, grey, yellow, orange, green, purple, brown, golden etc. Variations of colours were derived from a combination of different coloured warp and weft yarns. This was followed by the preparation of the warp. The weaver then passes the warp thread through the reed. The balucharis are woven in a specific Naksha loom. The weaver interweaves individual weft yarns with warp yarns. The saree is woven with the face downward. The weaver checks the design in the mirror placed at the bottom.

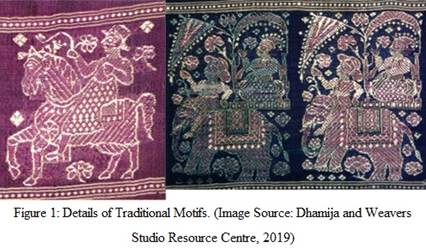

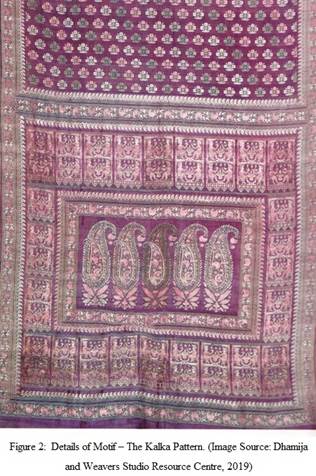

The traditional motifs and patterns used in baluchari sarees were derived from the miniatures of the Murshidabad School of Painting. An influence of European clients is also noted. Scenes of Portuguese battle shows, Nawabs and Begums smoking Hookah, and Europeans riding horses can be seen. The Kalka pattern was a central motif. The handwoven kalka motifs were a little slanted and bore the authenticity of the weave. The intricate and detailed kalka motif often emerged as the adaption of the tree of life. One of the most prominent weavers of baluchari was Dubraj Das, who was known for weaving his sign into the motifs of the saree. The style of signing the saree by the weaver comes from the Nakshabandas of Varanasi.

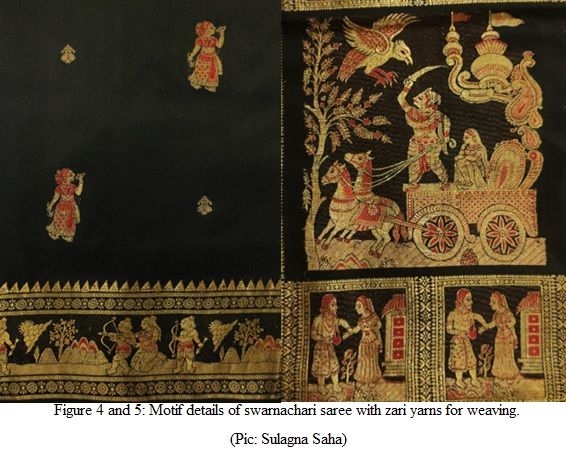

Despite its aesthetic and artistic splendour, the tradition of weaving baluchari gradually declined due to the rise of demand for western machine-made sarees among the affluent clientele. The death of Dubraj Das was the final blow. It was only in the 20th century that the craft was revived by the efforts of Shubho Thakur from the Tagore family. He set up the craft at Bishnupur with the help of master weaver Akshay Kumar Das. The newly revived Baluchari motifs shifted from the traditional styles of Murshidabad painting and were focused on scenes from mythological stories of Ramayana and Mahabharata. Motifs are also inspired by the terracotta temples of Bishnupur.

The design of the baluchari saree comprises of the densely weaved pallu or anchal, the intricate border and the zamin or the body with smaller motifs. The border also separates the zamin and the anchal. The warp and weft yarns are generally of two different colours. The motifs are often weaved with undyed silk yarns. A variation of baluchari sarees is called ‘swarnachari’, where zari yarns are used for the motifs.

The essence of baluchari and swarnachari is eternal. A number of new-age designers have used these sarees to create contemporary designs. In an exhibition, ‘Baluchari Bengal and Beyond’, organised at the Birla Academy of Art and Culture, Kolkata in 2016, about fourteen designers came together to showcase their modern baluchari designs. The designers included Kallol Datta, Dev R Nil, Rahul Mishra, and Aneeth Arora of Pero. The designs comprised of layered jackets, stripped palazzos, jacket dresses with floral motifs, draped dresses, as well as home furnishing products like bedcovers, quilts and cushion covers.

The art of baluchari weaving stands as a testament of the way art forms evolve. This evolution adapts to the cultural practices and aesthetics perception over time.

Comments