Politicising and weaponising trade invariably result in unforeseen repercussions, even when instituted with the best intentions. So it is with the sanctions on Xinjiang province imposed by the US Government under the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA).

It is said that the Government of China has committed serious acts of violence against the Uyghur population in Xinjiang province. However, how serious and how terrible are these acts is open to dispute. Nevertheless, the US Government has gone on record to accuse and hold the Chinese government accountable for genocide and human rights violations.

The response by the US Government has been a legislation that reads: “EFFECTIVE FROM 21 JUNE 2022, THE UYGHUR FORCED LABOR PREVENTION ACT ESTABLISHES A REBUTTABLE PRESUMPTION THAT ANY GOODS, WARES, ARTICLES AND MERCHANDISE MINED, PRODUCED OR MANUFACTURED WHOLLY OR IN PART IN XINJIANG, OR PRODUCED BY A PROPERLY IDENTIFIED ENTITY, ARE MADE WITH FORCED LABOUR AND THEREFORE BARRED FROM ENTRY INTO THE U.S. UNDER SECTION 301 OF THE TARIFF ACT OF 1930.”

Under the circumstances, barring imports would seem to be a reasonable action. However, the results of this action go much further than penalising China.

Bearing in mind that 80 per cent to 90 per cent of all cotton produced in China is grown in the Xinjiang province, this action has had far reaching repercussions, penalising other countries and groups where the US has no fight.

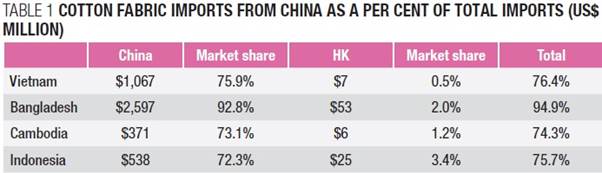

As you can see from Table 1, the 4 listed countries rely on China for between 74 per cent to 95 per cent of all cotton fabric imports crucial to their garment export industries.

Where can these countries go to replace the needed cotton fabric? As we can see from Table 2, the immediate answer is nowhere. Looking at the two largest cotton fabric suppliers after China - India and Pakistan - we can see they simply do not have the capacity. Their combined exports - $2.5 billion - are but a small fraction of China’s $12 billion.

Where can these countries go to replace the needed cotton fabric? As we can see from Table 2, the immediate answer is nowhere. Looking at the two largest cotton fabric suppliers after China - India and Pakistan - we can see they simply do not have the capacity. Their combined exports - $2.5 billion - are but a small fraction of China’s $12 billion.

The loss goes further than the Asian garment exporters. These repercussions go all the way to the US whose citizens will have to pay for their government’s policy in the form of higher retail prices.

This, in turn, raises a fair question: We can understand punishing China for their terrible policies in Xinjiang, but why is some guy in Cincinnati Ohio who wants only to buy a T-shirt and jeans being punished? He has not violated the rights of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, nor has he committed genocide. Indeed, more than likely, he has never even heard of Xinjiang or Uyghurs, yet his government is holding him responsible by making him pay the price. This is the invariable result when governments move to politicise trade.

The difficulty is that once governments move the political lever, that lever becomes stuck.

In the case of forced labour in Xinjiang, while the US law allows imports of materials from Xinjiang, provided the garment exporter can prove that the materials were not produced by forced labour, virtually no garment exporter from any garment exporting country has been able to provide sufficient proof to satisfy the US Government. The reason is quite simple, anyone, including the President who allows any imports that include Chinese materials will be attacked FOR BEING SOFT ON CHINA. You can understand why no one in government wants to spend political capital on support for the US enemy numero-uno.

The question remains: Where do we go from here?

The following is speculation.

I believe we are about to see a return to SUBMARINING.

Submarining is an decades old strategy, purposely designed to circumvent import restrictions. At its height submarining was a truly global industry. During the MFA quota restriction period (1963-2005) submarining was a multi-billion-dollar industry. After the quota phaseout submarining became much reduced. Although, as we will see below, it never disappeared, and to this day shows up in the most unusual places.

Re-Exporting

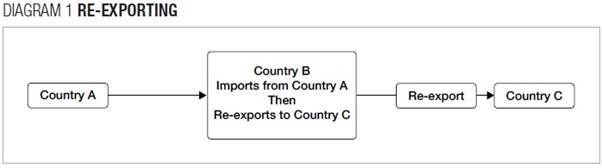

Table 1 includes exports from Hong Kong. These are not exports, but rather re-exports. Under international trade law, if country B imports goods from country A and exports those goods to country C, without making any changes in that product, country B charges no import duty.

There are legitimate reasons for re-exports. For example, Hong Kong is home to one of the world’s largest ports. Factories in South China - adjacent to Hong Kong - will send their goods through Hong Kong to the international port. Since the product undergoes no change while in Hong Kong, it is considered to be a re-export and therefore Hong Kong cannot charge any import duty.

Submarining

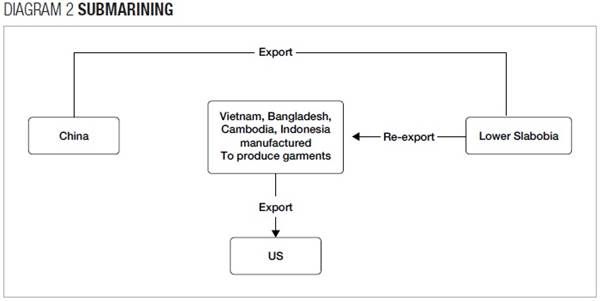

This is something else. Let us say that China wishes to export cotton fabric to garment exporting countries such as Vietnam, Bangladesh, Cambodia and Indonesia, but cannot do so because the US has imposed restrictions on imports of any goods from any country using materials produced by forced labour in Xinjiang province, China.

The solution is relatively simple:

• China exports the materials to some third country e.g., Lower Slobbovia.

• Lower Slobbovia then re-exports the materials to garment exporting countries, e.g., Vietnam, Bangladesh, Cambodia, or Indonesia.

• These garment exporting countries are then free to export cotton garments to the US because they have documentary proof that all cotton materials had been imported from Lower Slobbovia and no materials had been imported from China.

Submarining is universal. Here is an interesting example currently involving the US.

Submarining is universal. Here is an interesting example currently involving the US.

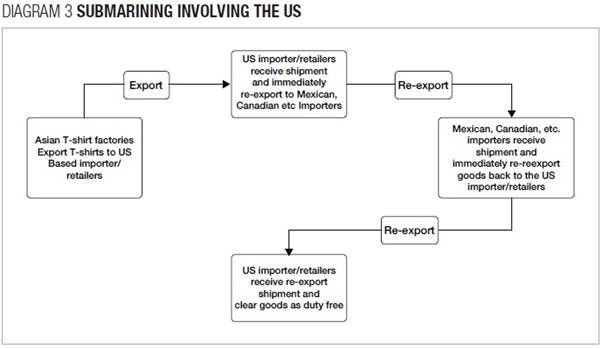

The United States is a major importer of T-shirts. The problem is that the import duty on T-shirts is quite high.

Cotton T-shirts: HTS 6109.10 = 16 per cent

Other T-shirts: HTS 6209.90 = 32 per cent

To avoid the nasty import duty

• US importer/retailers will import T-shirts from Asian T-shirt exporting countries.

• On arrival in the US these same importer/retailers will re-export the T-shirts to importers in countries such as Mexico, Canada, etc which have free trade agreements with the US.

• The Mexican, Canadian etc importers will in turn re-reexport the same goods back to the original US based importers/retailers who had originally imported the T-shirts from the Asian T-shirt factories and then had re-exported the T-shirts to the Canadian, Mexican etc importers.

• At this point, the T-shirts have been rendered duty-free.

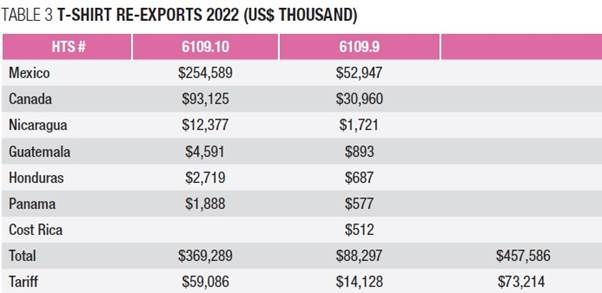

This is not an academic process. If we look at the data for 2022 in Table 3, we can follow the transactions. Goods are imported, then re-exported to Mexico and Canada (USMCA) and Nicaragua, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, Costa Rica (DR-CAFTA).

Table 3 shows that the importer/ retailer saved $73 million, in tariffs for the year 2022, on a single product.

I am 99 per cent confident that China’s textile exporters will move to submarining, if they have not done so already. Afterall China invented submarining.

The good news is that submarining will not only benefit China but more importantly those Asian factories that rely on China’s cotton textiles, to say nothing of the poor guy in Cincinnati Ohio who will no longer be forced to pay the US government’s-imposed retail-price premium.

Truly a win-win situation.

Comments